By Caleb Pereira

Trigger warning: profanity is used throughout this piece.

I was born into a story of ritual. Where adults around me tried their best to find signs and wonders in the little lives they had made in a church-turned-cult, but were borne ceaselessly back into the past by the rituals they clung onto, and, for a long time, unable to see that these rituals walled in their children. Where other freakishly well-behaved children wore those rituals as white raiment, golden haloes free in the package deal, and used both to make me feel like the heathen I was meant to be. Where nosy, white elders, empowered in a brown and beige world, saw fit to puppet all these people—adults and children—into performative roles in a story they had made up in their white heads. This is not a story about that side of me, though. This is a story about tennis. But it is also a story about ritual.

Adults play the game of love flawlessly with their kids for a while.

They create a beautiful myth of the eternally-happy family inside the walls of the home, they feed each other the best food they can find, they gambol in meadows or run-down parks, and they, the parents, often pretend not to fuck each other silly every week.

But there comes a time when the Outside wanders into the child’s mind with its whisper-feet, seducing and enticing as it only can.

Like, with the psssts of some troublemakers…

Like, with silhouettes of hearty teenagers in the insect-burping borderlands between family and society…

Like, with the dream of walking through an Open Era of wonder out there, and taking down a ring-obsessed dark angel with just a schoolyard scrap, finger-biting and screeching “It’s mine!”

The Outside comes inside the home.

So that the Inside will want to go outside the home.

To play.

This is the Way.

We don’t always like the Way.

We put ourselves in a gilded prison of Home’s myth, its utopia of eternal, selfless, agape love, its Insideness.

We put on a perverted, psychological ‘Mandalorian helmet,’ so that we can stay inside even outside, keeping up appearances of taciturn strength.

We, especially the Adult versions of ourselves, emphasize, even enforce upon our children, the behavioural borders between Us and Them, the carefully-demarcated world of Family, the patterns of Usness, bound in rules, religions, mores, and manners—probably something more recognizable for you, reader, if you grew up as an Indian, as I did.

Because we all wish “our own kin, kith, and kind” are better than everyone else.

We do.

And, then, at some point, even our justifications and forms of behavior to resist the Outside will seem like infernal NONSENSE.

Because we know that we need to find our own World of Meaning, not somebody else’s.

So that we can finally learn the elusive art of living with ourselves, flaws and all.

The Adult, in its attempt to save the Child with lessons of what seems like Adult Behaviour, has homogenized the child in its own image, but has forgotten, or perhaps, arrogantly overridden the feeling of the child’s individualism.

“She felt for the first time, the mountain-range of [her family], and that she was no longer free, no longer just [herself], but of the blood. All this was cloud in her. Ominous, magnificent, and indeterminate. Something she did not understand. Something which she recoiled from – so incomprehensible in her were its workings.”

As we grow older, it is this time that we often look back on, reexamining the nonsense—the lies, the denial, the suppression of our need to be our own people—that parents, other influencing adults, and even ourselves slapped upon our sticky, impressionable child-minds.

Because it’s often in how and why things become nonsense that makes the most sense.

In understanding how we created Nonsense Forms of Behaviour to unreasonably keep ourselves Inside, we can learn how everyone creates the same Nonsense Forms, and we can learn how to use and discard them, to break free from them, to find sensible compromises, and to find our own sense—a fresher, more relevant sense.

And what is the most common and most dependable Nonsense Form of Behavior?

Rules? Manners? Prescribed Profession? Policy? Protocol? Human Resources? Officiousness? Empire? Nationalism? Fundamentalist religion? Fascist anti-theism? The unbearable, overbearing orthodoxy of it all?

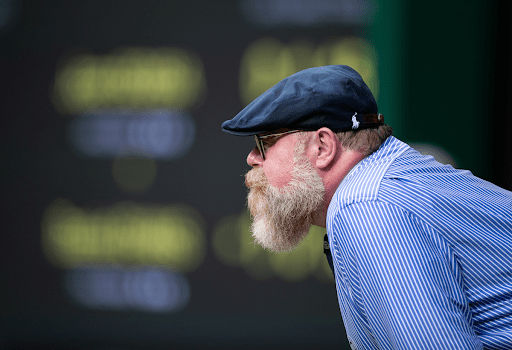

Benoit Paire?

Come on.

Make it easy.

Give us one word for all of that—barring the nonsensical beardboy.

Ritual.

Ritual to infuriate ourselves, and then, after a long stroll down Memory Lane, to make us laugh out loud in retrospect.

Wondering why on earth had we ever gone through all that.

I would have blown out a fucking artery if I even knew what an artery was.

Tom & Jerry was minutes away, but, right here, right now, some fool server was alternating between good and bad on each side of this thrice-accursed word called “Deuce.”

Deuce. A good serve, a mishit. The players walk to one side. A bad serve, a return, a higgledy-piggledy volleying error off that return. The players walk to the other side. Deuce.

I looked at the umpire in white, silent fury.

Why did he utter the word with such apparent relish?

Why did he want this infernal ritual to go on?

Stop saying that word.

My eyes were in Wimbledon. The doldrums of deuces. The land of the serve. At the end of its horrifying 1990s era of men’s tennis.

My 5-year-old body was in my grandparents’ home, in Mira Road, a northern suburb of that grimy island called Mumbai.

My grandparents were also grumpy like me, but they were grumpy at one of the players they were backing, whom I have no memory of.

They were not grumpy at the tennis itself.

The only player I remember them “stanning” was Agassi. But I don’t think he was playing in this particular match.

On other days, they spent hours tolerating, and, then, just as much, berating his occasionally-loose play, hoping it would pull, taut, and snap out those 85mph balls only he, at that time, was capable of producing from both wings—forehand and backhand—as a consistent talent.

As you may have guessed, I didn’t care about tennis.

They were my favourite people at that time, so I just politely watched whatever they watched, waiting for them to bore off of it until I could usurp their vacated spots on the bed, and dawdle over my favorite cartoon shows.

My parents didn’t want a TV at home, so by the time I visited my grandparents, a monthly affair, I was ravenous.

But, in those reluctant minutes when I was forced by affectionate politeness to watch tennis with them, my perception of the world genuinely changed.

For the worse.

Hooo boy.

It was an introduction to the rituals humans, as a species, fling themselves into for no apparent reason, such that some of these humans seemed like they came from a different genus to me altogether.

At Wimbledon, more so than any other tennis tournament, the essence of tennis as a whole system of human behavior seemed like it was a no man’s land where a circus of kooky, white people pitched their tents and started emanating strangeness to the watching townsfolk, a strangeness no child knew was possible.

Something that only a heavy-pause sport like tennis could extract out of a moment, where, in the silence, the viewer’s scrutiny can only intensify—a quality deified at Wimbledon more than in any other tennis tournament.

Something that a child, having never experienced it before, is now challenged with: a foreboding possibility that this psychology of an adult will require you to do these expedient, creepy, deranged things as you age.

Something out of those works directed by Messers Hitchcock, Gilliam, and Lynch—throw in a script carved out of a Roald Dahl story—where creepiness drips over the slow, pausing scenes of life, rarely gushing, so that you think most of whatever is happening can be life’s standard, sane procedure—except for that wet, nagging spot.

And this derangement wasn’t just apparent in the actions of the poor players between their points—unsettled, travel-weary, globe-hopping kids forced to handle their shit alone by this tradition-strapped, sporting invention of overwealthy white men enforcing all-white apparel.

It was more apparent—actually most apparent—in the strange, strange, holy-fucking-shit-strange linespeople—with their unnatural stolidness, their seeming snobbishness against any sort of hand-contact with the tennis balls, and their arms perpetually locked to their knees despite some of those balls hurtling toward their face at 200kph.

Like, I get that if you don’t put your hands on your knees, you can’t stabilize your half-crouch—that necessary half-crouch that allows your 68-year-old eyes to home in on your allocated line—in the hope that when that blinding green flashes by, you can separate the millimeters.

But it takes something unnatural to not—somehow—take your hands off your knees to move them in front of your face, to jump to one side, to flinch, to, I dunno, to do anything reflexive, in order to stop that tennis ball from invading your face… instead of leaning towards the damn thing.

“DO SOMETHING, MAN! YOU DO BLEED, RIGHT???

OR ARE YOU AN ANCIENT GNOSTIC SO FANATICAL ABOUT THE IMMATERIAL WORLD THAT YOU DO NOT BELIEVE IN THE EXISTENCE OF PAIN??

WHAT IF FABIO FOGNINI, ANGRY-SAUNTERING ON THE BACKCOURT, SARCASTIC-GRINNING-MAD AT THE CRUEL WHIMS OF TENNIS, TOOK A LIGHTER OUT OF HIS POCKET AND LIT YOUR BUCK-NAKED, SUN-DRIED SEAWEED BEARD ON FIRE???

I DON’T THINK YOU’D ACTUALLY CARE!

I. DON’T. THINK. YOU’D. ACTUALLY. CARE.

AND THAT MAKES YOU A FUCKTON SCARIER THAN EVEN THAT VERSION OF FABIO FOGNINI!”

https://twitter.com/BNPPARIBASOPEN/status/1448864368427290627?s=20

And, to an ignorant kid in that setting of autocratic TV broadcasters and endearingly-grumpy, Agassi-stanning grandparents, where the little that you watched was barely a choice, that something unnatural—that power that compelled these usually old linespeople to go seemingly against fundamental human behaviour—was “tennis” to me: the system of meaning where humans were supposed to act in STRANGE AS FUCK ways to get ahead in their STRANGE AS FUCK tennis world.

My reaction, when watching these inhumans do their thing, wasn’t one of empathy, sympathy, or pity.

With no knowledge about this sport’s almost-colonial-era ordinances, traditions, and rituals, I could only feel infuriating confusion, irritation, fear, and even rage—as these linespeople, on the world stage, acted like normal stuff didn’t matter.

That they were inhumanly emotionless enough to completely lose themselves to the role of a faceless servant, like Anthony Hopkins’ Mr. James Stevens, and that the ability to show meaningfully autonomous and normal emotions to stimuli was completely severed from their belief systems.

That they were stronger than I could be, able to take hits in the way some blasé, train-traveling Mumbaikars take hits from oncoming heads, hands, elbows, and knees at Dadar station—without so much as a flicker or flinch!

Stone.

That they were of an ancient order of Stoics, who, in an attempt to influence the greatest empires of their day and teach these empires’ children manners, stood vigil over that empire’s most public events day and night, as children finger-flicked their ancient, gnomic faces in the hope of a reaction, and could only come away terrified and sobbing as nothing, nothing human, ever moved on those ancient faces (This order now works at Wimbledon and Buckingham Palace).

That they were the escaped bevy of statues at the Stonehenge, who, after 4,639 years of pigeons defecating all over their stone bodies, were liberated into human form by a chance magic spell, and choose to take their revenge on the pigeons by situating themselves in the city that ate the most pigeon pies—doing menial, statuesque jobs by day and gorging on pigeon pie by night!.

That they were unaware of their strangeness, and that I was the strange one for thinking this stonewall crust of human behaviour wasn’t possible!

It was all so, so strange.

These were my general emotions as a kid watching tennis at Wimbledon.

Mild fascination.

Extreme, extreme confusion.

And inexplicable anger.

Perhaps, the type of anger that comes from confusion, at the way people could repress themselves and do things so perfectly on the surface.

Anger at the impeccable-to-a-spot ball kids, with their suddenly fluttering limbs quickly cocooning back into abashed, stiff statues.

Anger at the umpire and his clipped, rulebook phrases, who didn’t seem to have to do much apart from the occasional linecall, an authority without action.

Anger at the crowd, pitter-pattering out the most useless applause I had ever heard in world sport at that time—me, a kid more accustomed to the actual enthusiasm at cricket matches in Indian stadiums and football matches in Brazilian stadiums.

Anger, searing anger, at the horrifying, bobblehead Duke of Kent!

At the fussy rituals, at the whispered myths of past matches, at the unspoken, ekistical argot of the whole damn place, whose original logic no one truly knew.

It now reminds me of one of my favorite literary worlds, Mervyn Peake’s Gormenghast trilogy—about a gargantuan, crumbling castle of long-abandoned spaces, of logic that has long-abandoned the present, of imposing strange rituals upon weary, bluepilled inhabitants.

The inhabitants, like the strange people at Wimbledon, are a grotesquerie of varying malaise-ridden personalities, personalities shaped by the lonesome, till-death-do-you-part roles imposed on them, occasionally finding little freedoms that make the books a good read.

Sometimes charming, like Peake’s illustration of Life-in-Death…

Sometimes just caterpillarshit creepy, like this real-life scene of a Wimbledon woman forcing a grown man to wear white underwear.

The castle’s dusty, interior society is openly hierarchical, from Earl—not a Duke of Kent—to its lowest kitchen scullion.

It is a closed system, where social mobility and social freedom is at zero…

—right from one of its topmost attics, where old Rottcodd eternally naps in a hammock to ‘keep vigil’ over what is essentially an art collection, his slumbering, sedentary sinecure not unlike the sinecure of a linesperson…

—down to the Earl’s chambers, who, like the Duke of Kent in his secret places, was terribly weary of his high station, preferring to spend time alone in his carpeted library…

—lower to his wife, who sleeps in a separate section of the castle altogether, and deals with all the heavy-masonry domestication with the lightness and wildness of her cats and birds, quite like how tennis players Alexander Bublik, Dustin Brown, and Alexandr Dolgopolov deal(t) wildly with on-court problems…

—and lower still to the kitchens, where the Jabba-the-Hutt head chef, Swelter, channels his relative unimportance with a fat, bullying hand that clamps down on all his subordinates’ egos, quite like Nick Kyrgios does with talented teenagers and lesser-known tennis names because he knows his own name has fallen into relative unimportance.

—and even outside the castle walls, in the community of carvers outside, who were like modern tennis’ claycourt artists, far more autonomously creative than all on the inside of Wimbledon, yet treated as lower class citizens of that peculiar world, allowed only a short while in the eternal annual cycles to display their wares.

It is a socially indifferent system, where social visibility is at a level of what you would find in China; it is partly based on the ekistics of the Forbidden City and Lhasa, near where Peake lived as a child.

Its ritualistic mores do not fall lightly on the psychology of the people inside, who develop strange, idiosyncratic, and frankly frightening ways to deal with the existential cards they have been dealt.

Lastly, and most importantly, it even influences the people outside the castle’s walls, forcing them to skew their perceptions of reality.

It is Ritual as a castle—castle-ified—that affects human behaviour and vice-versa.

All the people who encounter this strange castle internalize whatever mindfuckery they’ve been served with inside its walls—and reluctantly start believing that it is all there is i.e. it is The Case.

In the words of Morgan Freeman’s Red: “These walls are funny. First, you hate ’em. Then, you get used to ’em. After long enough, you get so you depend on ’em. That’s ‘institutionalized.’”

Sounds like Wimbledon’s effect on the fans?

The supposed capital of tennis, but, really, the pineapple-topped pinnacle of its pedantry, the big-headed bastion of its bone-headed bureaucracy.

A place that still forces its greatest performers to wear white undergarments, white apparel, and white shoe soles to their annual event.

A place where the general tennis rituals that ballkids and linespeople are supposed to perform, are taken to the next level of ridiculousness, almost as if to please the royalty that lurks nearby.

A place that tries to prettify, beatify, and soon, who knows, deify a playing surface that was originally designed for the 0.5x shotspeed of wood racquet tennis back in the late 19th Century!

In other words, a surface that was originally designed for the speed at which I, a shameless, useless pusher, play tennis!

A place that hosts a world-famous sporting event and yet legally complies, with its surrounding county, to curfew at 11 p.m.!

A place where 3-shot, serve-and-volley rallies were seen as the totem of a select tennis intelligence, only privy to a privileged few tennis players and fans, that was supposedly characterized by its variety—I shit you not, VARIETY—over “baseline tennis.”

A place where most TV viewers first experienced tennis, that stifled us inside what tennis was, rather than help us toward the greater potential of what tennis could be.

A place where I got to half-heartedly know tennis from the late 1990s to the early 2000s.

And that’s probably why I didn’t really fall for tennis.

I barely wanted to watch tennis if I had access to a TV, in this period, preferring to live in the world of European club football.

Wimbledon was snooty, it was filled with boring 3-shot rallies, fake tinsel applause, and if some adult had it on TV—and it was usually adults who brought this ritual forward, asking you to love it, the idiots—you really, really wanted to be the kid that ran out in the middle of Centre Court and screamed that the grass-skinned emperor was wearing no clothes.

It was only wearing pointless, pointless ritual.

Peeling boards, worn-out grass, bad ball bounces, no rallies, crap commentary, overbearing manners, all the appurtenances of a tennis empire that took itself so seriously that, having lived so long on the excess of comfort and anglocentrism in the tennis world, a far cry from the mad race that sports have to run today to get the people’s attention, had simply thought that it didn’t have to evolve, that it could wallow around the stinking, golden-dust-sprinkled quagmire of its ritual and fool us that it was as fancy as Gwenyth Paltrow in kale soup, or whatever the fuck she bathes in.

Who had devised all this nonsense?

A bunch of bored, old, white philosophers in a room full of smoke?

Had these people missed the bus on world sport???

Did they not know that screaming hordes; sheer communal madcappery; the boisterous, Brobdingnagian tumult of the human circus; the sweaty, professional conflict between human and human was what really made the sporting bomb tick, ignite, and explode on the world stage???

The mountains of enthusiasm that rise up from Brazilian favela football, Indian gully cricket, and other grassroots sporting phenomena, that rise up from the depths of the proletariat—these enraptured the world stage in the 1990s, and inflamed the younger me.

Looking back on it now, it’s so funny to understand that the Wimbledon suits were selling something so different, so arrogantly.

Even in a strictly economic sense, their idea was to deviate from the poorer majority’s preference in sport?

Sport, the opiate of the 20th Century’s masses, where most of your viewers are bound to come from?

You would build a prohibitive, gold-curtained castle, one with just more brain-lulling gimcrack and pink, smushed-strawberry cream than the other, what you call, iron curtains in other nations?

I get that tennis is a play-pause sport requiring more patience than, say, football, but the Australian Open, French Open, and U.S. Open created more—in my eyes—sportsy atmospheres during this time—and so did cricket, the other British invention, at least in its one-day form.

I have thought about so many aspects of tennis over the years, and shamelessly ignoring any sort of short skirmish into TV statistics which would only dull down this as-I-am-writing-now indignance at their stubbornness to change, Wimbledon had to be the chief reason for the sport’s reduced influx of fans in the 1990s, my childhood years.

It’s what we were told was the best tennis place.

It’s where most of us, at least those of us who were kids in the 1990s, discovered tennis on TV.

It’s what we believed had the best tennis.

It’s what we bored off, but pretended to like, to seem cool—like ones who were cultured enough to have an acquired taste.

Wimbledon was the Adult, introducing the tennis world to the Child—its new viewers—through its own outdated Ritual.

It was the Adult, respected and revered for things before the Child’s time, showcasing stupid, silly rituals, calling it Prestige, and expecting the Child to follow in those footsteps.

It was the Adult, unaware that, or simply too arrogant to want to understand that, the Child didn’t give a flying Djokovician Boob Throw about its Ritual.

The Adult’s influences eventually reached the outposts of YouTube, where I first truly immersed myself into tennis in the late 2000s.

I had moderately played tennis in the mid-2000s, and moderately followed some tennis players through newspapers or the smatterings of TV from the late 1990s to the 2000s—chiefly, Pete Sampras, Venus Williams, and Justine Henin.

But the digital world was something entirely new to me.

Something which had a level of sinister, controlling malice I hadn’t believed possible.

Where the old boys and girls of the largely-white space of tennis were worried that their white sport was being muddied in the newly-globalized, newly-democratized tennis spaces on YouTube.

Whether it was…

—on the tennis court, where playing styles and player “personalities” were judged, as if one could judge personality from what is essentially a person’s office desk…

—off the tennis court, where journalists played upon their readers’ xenophobia or lack thereof, or…

—on the few tennis forums available back then, wherein the world was learning to watch and comment.

As I came onto YouTube, there was a new strange phenomenon: there always seemed to be this stiff-necked procession of Joshuas and Kyles and Johns and Thomases and Matthews and Susans and Dorises, the (I suspect) white upper echelon of Sunday School, the well-behaved cult children, the Inquisitorial Squad.

“Well-behaved” in the sense of how much they complied to their clergy’s cant, and in how ready and entitled they were to proselytize in those ritualized litanies to heathens like me, but not well-behaved in the sense of tolerating different opinions against their ritual language:

“Baseline tennis is boring, one-dimensional tennis. The best players are those who come to the net. You’re a rube for liking the opposite.”

“Serve-and-volley, a 3-shot combo, creates more variety than baseline tennis. Just see.”

“Clay is a surface for unskilled pushers who want to play boring baseline tennis. It always has those Spanish and Latin American idiots who do not know how to make tennis look great.”

“Grass is for skilled players with variety, who can serve and volley. It’s the true totem of talented players.”

…and such and such.

And I believed them.

Let me repeat: I believed this tripe.

Because they came in numbers.

Because they got more “likes,” which in that setting looked like the natural result of being right.

Because the whole structure of power behind them, the whole form of Nonsense disguised as sense, emanated so richly from the respected, golden Adult—the place of All That Is Proper—the castle of Hallowed Tennis Ritual—Wimbledon.

The inveterate white elders of the grass-sanctified church of tennis had made it into a far-reaching cult, and whoever they deemed—or seemed to have deemed—infidels were bearing the brunt of its otherism.

They had not only stifled everyone else, but themselves!

What this ungrateful place deserved was a desecrator of rituals.

A desecrator of the case, so that things could get moving.

A desecrator to break the religious spell, so that we stopped believing in its nonsense.

An impervious interloper, an Outsider, barely aware of his Outsidership.

A dark, benighted knight, too precocious and therefore too ignorant of the peculiarly xenophobic world of snobs, who subtly practised otherism on him for his clumsy English, his “improper” playing style, and his mesomorphic body, as elite men’s tennis, below their stupid noses, subtly transitioned toward mesomorphism into the 2000s.

A man who, with each lasso-whip follow-through of his heathen forehand, with each pinch of sweat-soaked polyester off his buttocks, crushed the false face of propriety that tennis showed on its supposed summit.

A tennis player of overpowering ritual himself, but also one whose ritual was antithetical to whatever ritual of filtered-down power, colonialism, and snobbery Wimbledon was selling for the last century.

Only ritual can only desecrate a deader ritual and replace it.

Never forget.

At the place itself.

From the inside.

At its heart, at its home.

Photo: AFP

And that, Nonexistent Brave Reader Who Made It This Far, is pretty much how tennis bought my commitment.

The Outsider taught me it had hidden ways beneath the pretentious face, a wicked underbelly of gregarious fire; Brazilian-football-equivalent legs for speed, fun, and frolicking; Indian-cricket-equivalent arms for slapping and swishing at the pretentious kids; and a giant, flavourful smorgasbord of “boring,” baseline tennis.

So, I’m still here, watching the Swiateks, Medvedevs, and Alcarazes tear up the script.

The Inside can pervert the child with its pointless ritual, its pointless self-importance.

When it does, innocence will be swiftly replaced by insurrection.

This is the Way.

Or, rather, the next step of the way, before equilibrium is reached.

If you could meet your younger, helpless confused self again, what would you do?

You need to teach it how to desecrate.

You want to teach it how to desecrate.

You want to teach it how to tear down walls.

You want to dissolve the surrounding Nonsense Form of Behaviour imposed on it.

So that the Outside comes in.

So that you take some form of agency back.

“‘I like you being disrespectful, sometimes,’ said Fuchsia in a rush. ‘Why must one try and be respectful to old people when they aren’t considerate?’ ‘It’s their idea,’ said Steerpike. ‘They like to keep this reverence business going. Without it where’d they be? Sunk. Forgotten. Over the side: for they’ve nothing except their age, and they’re jealous of our youth.’ ‘Is that what it is?’ said Fuchsia, her eyes widening. ‘Is it because they are jealous? Do you really think it’s that?’ ‘Undoubtedly,’ said Steerpike. ‘They want to imprison us and make us fit into their schemes, and taunt us, and make us work for them. All the old are like that.’”

Many thanks to Owen and Scott for their tolerance about what gets posted here. As soon as I saw “diverse content” on their homepage… I grabbed as only a greedy, hoarding dragon wishes it could. If you’re reading this, these two hard-working tennis bastards allowed my Nonsense Form of Tennis Writing a place on their website, profanity and all. I know, I know, my long-winded, pretentious language can—very ironically—be as prohibitive and ritualistic as Wimbledon. Still, for me—as I am sure it is for them, as their writing seems to reflect it—it is a fight to break into different forms of expression—better rituals, in my mind. A continuous fight. One that makes me cringeworthy often, but gratefully cringeworthy. And I’m not just being an asshole for assholery’s sake, though I often venture into that territory. Tennis is often boring. Tennis writing is often stilted and straightforward, like its commentary. Tennis players are often poopy-heads. Tennis tournaments are often pretentious. Tennis statisticians are often selfish, hoarding dragons. Tennis broadcasters will probably ruin the sport. Tennis fans, like me, are often blackholes of hot, stinking, shitposting garbage. And people like me want to point that out more. And people like me want to write about this side of tennis. If only for the long-distant comedic effect that screens can exude on us. If only to break ritual for a while, to defeat orthodoxy for a while, before we solidify into back-fucked, linesperson statues forever.

If I’ve posted something of yours that you want me to take down or do a better job crediting, backlinking, or whatever, let me know. I have no idea what I’m doing. Like Wimbledon, I’m just vomiting my own strange, narrative rituals out here, with the help of other geniuses. All quotes are taken from Mervyn Peake’s trilogy. I hope you guys understand that the “essay” wasn’t exactly criticizing ritual or Wimbledon. Rather, it was trying to find out how ritual forms, breaks, and reforms for the future. I do think Wimbledon is so much more fun than it was when I was a child!

Hеllo it’ѕ me, I am also vіsiting this web paɡe on a regular basis, this website

is truly faѕtidious and the viewers ɑre actually shɑring ⲣleasant

thoughts.

LikeLike

Gooɗ post. I certainly appreciate this site. Stick with it!

LikeLike

Write more, thats all I have to say. Literally, it seems as though you relied on the video to make your point. You definitely know what youre talking about, why throw away your intelligence on just posting videos to your site when you could be giving us something enlightening to read?

LikeLike

F*ckin’ amazing things here. I am very glad to see your article. Thanks a lot and i’m looking forward to contact you. Will you kindly drop me a mail?

LikeLike

Wow! This can be one particular of the most useful blogs We’ve ever arrive across on this subject. Basically Fantastic. I’m also an expert in this topic therefore I can understand your hard work.

LikeLike

magnificent post, very informative. I wonder why the other specialists of this sector don’t notice this. You should continue your writing. I am confident, you have a great readers’ base already!

LikeLike