It’s been a couple weeks since Carlos Alcaraz beat Novak Djokovic 1-6, 7-6 (6), 6-1, 3-6, 6-4 in a scintillating Wimbledon final. I wrote a piece the day after the match, which you can read here. But matches like this, with so many twists and turns, deserve a closer look, hence my decision to closely rewatch the match and record a long list of observations and thoughts. I will not attempt to write poetically in this piece (not that my attempts at that are ever successful). No, this is a space for nerding out over the match of the year. You will see hyper-specific point analysis. You will see theories. You will probably see stuff nobody cares about but me and maybe a couple others. Let’s jump in.

1. Did anyone have Carlos Alcaraz winning this match before it started? Hell, did anyone have him winning before he claimed the second set? Novak Djokovic had won Wimbledon in 2018, 2019, 2021, and 2022 (the tournament didn’t take place in 2020). He hadn’t lost a match on Centre Court since 2013, and that match came shortly after Juan Martin del Potro forced every ounce of strength from Djokovic’s legs in a four-hour, 37-minute semifinal, so there’s even an argument to disregard that one. Alcaraz was favored in his Roland-Garros semifinal with Djokovic, and even before full-body cramps crippled his chances of winning, he looked to be outmatched — on a surface that was supposed to be more favorable for him. On grass, a surface Alcaraz is a newcomer to and one Djokovic has long mastered, the former was a huge underdog.

2. Djokovic, all-told, didn’t have a great forehand day. But he has an all-time-great forehand. It’s not the greatest forehand ever, not by any means, given how shaky it was early in his career. It’s now one of the greatest ever, though. From the straight-up liability Djokovic’s forehand was in 2010, arguably no individual tennis shot has improved more in the past decade-plus. (Novak’s serve is another contender for most-improved.) Djokovic’s forehand is at its best when it goes toe-to-toe with another brilliant forehand, often thought to be better than his – it has more than held its own with Roger Federer’s forehand, with Dominic Thiem’s, with Stefanos Tsitsipas’s. With Alcaraz serving at 0-1, love-15 in this match, Djokovic chased down a very good crosscourt forehand and found an obscene angle for his own crosscourt forehand, which went for a winner.

Some shots get called underrated because they’re generally thought to be sub-par when they’re actually solid. Medvedev’s volleys are sometimes called underrated because people still seem split on Medvedev being completely inept at net or being a sneaky genius with his volleys (it’s probably a bit closer to the former than the latter). Djokovic‘s forehand is underrated because it’s genuinely one of the best in the world and doesn’t always get talked about as such. He can hit down the line, inside-out, inside-in, crosscourt, all with vicious pace when he chooses. He can find brilliant angles. His forehand defense may be the best ever. As a whole, the shot is bordering on legendary.

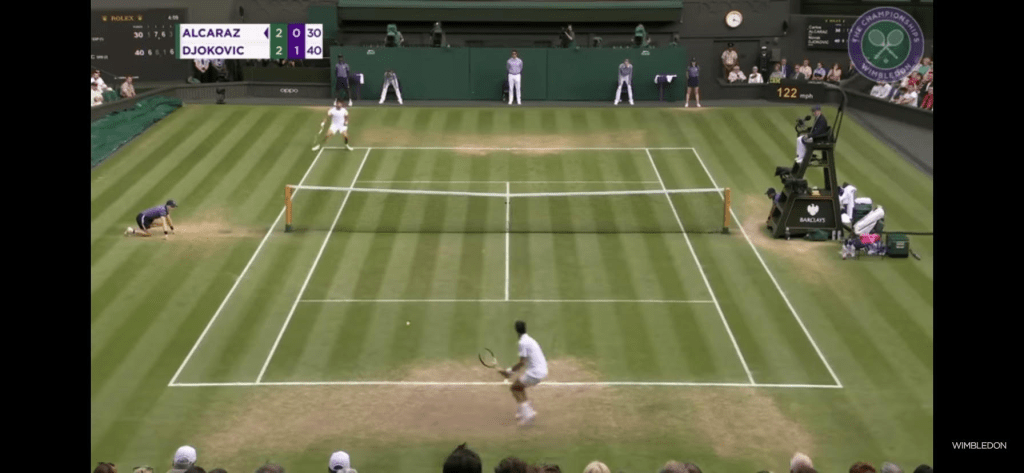

3. Despite Alcaraz having moments in the first few games, Djokovic got off to his trademark fast start, racing to a 5-0 lead. The fact that he lost this match notwithstanding: Djokovic still has the highest peak in men’s tennis. For much of this five-game stretch, Novak wasn’t even at his sharpest. But when he fleetingly hit his peaks, Alcaraz was helpless, like any opponent would’ve been. It all starts with the first shot Djokovic hits — he is a superb spot server, and the sheer depth on his returns freezes even players with the fastest reflexes on tour. From there, he dictates the point, and he’s not one to play with his food.

4. There is a point with Alcaraz serving at 0-5, 30-all in the first set in which he yanks Djokovic well outside the left doubles alley with a great angled crosscourt backhand. He follows it up with a backhand down the line that lands near the right sideline. Djokovic covers the distance from outside one sideline all the way to the other — significantly more than the 27-foot width of the court — in seven enormous steps, then launches into a long slide and recovers to get ready to return an overhead. That’s why he’s so difficult to hit through. Alcaraz had to put away a great smash to win the point.

5. After the first set — I’ll admit it — I thought the match would be a whitewash. Djokovic looked infinitely more comfortable than Alcaraz, and a comfortable Djokovic has pretty much never lost a tennis match. If you want a prayer of beating Novak, you have to knock him off his game for a while (and then play your very best tennis during his lapses). Alcaraz didn’t look capable of doing it, and I couldn’t imagine anyone else doing it, either.

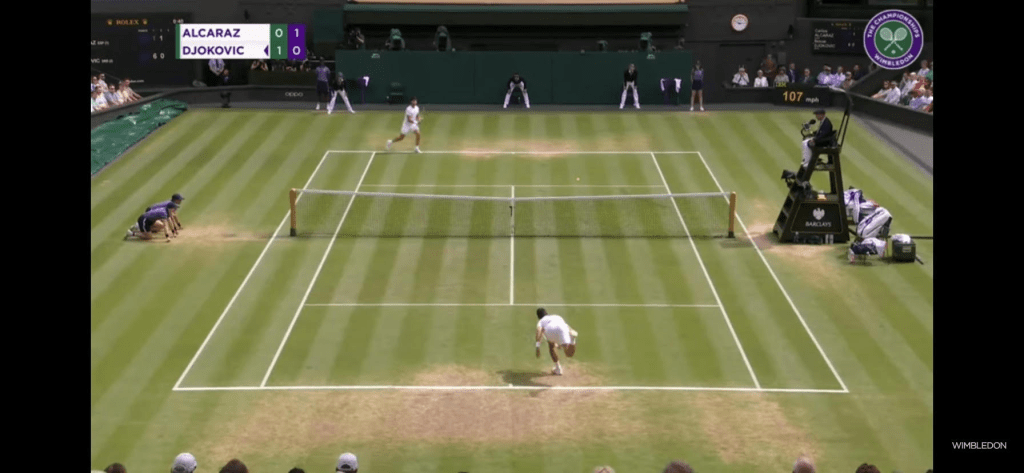

6. The opening set was a great advertisement for spot serving over power. Alcaraz was massacring serves all over the place at 130 mph, but they weren’t nearly as effective as Djokovic’s pinpoint-accurate deliveries in the low 120s. Professional tennis players are incredibly adept at handling balls flying at high speed. What’s more difficult is guessing which side to make a sprawling lunge to, then hitting a return at full stretch. Even if you guess right, your return is unlikely to have much pace on it if the serve hits a corner. There’s a reason Roger Federer was such a dominant server for so long, and why Djokovic is now — it ain’t power, it’s having an unreadable toss and great accuracy. Give me that any day of the week over the ability to hit 135 mph on the radar gun.

7. The most impressive touch moment Alcaraz had at net all day was the gymnastic backhand stretch volley winner at 15-all in the last game. The second most impressive came at 15-all in the first game of the second set. Alcaraz approached the net with an inside-out forehand; Djokovic zinged a backhand pass that dipped to Alcaraz’s feet before the Spaniard could even get inside the service line. Anyone not exceptionally talented at net is sunk in that position — it’s near-impossible to get enough pace or spin on a half-volley from mid-court to stymie a defender like Djokovic. Looking as relaxed as a bored student aiming a piece of chalk at a friend’s head across the room, Alcaraz somehow bunted a forehand half-volley directly onto the baseline. The depth on the ball handcuffed Djokovic into a netted pass. The volley wasn’t just an astonishing show of skill, it launched a mini-run for Alcaraz, who won 11 of the following 16 points.

8. Comedy watch: Djokovic hit a second serve straight into the middle of the wrong box to start his 0-1 service game in the second set. It missed by about six feet.

9. Alcaraz got sharper in the second set. He stopped banging the ball mindlessly and started waiting for openings. He’d crush the backhand down the line when Djokovic moved to his left, which opened up a gap to hit into, rather than trying to produce a winner with Novak standing in the dead center of the court. It was a smart adjustment, but I couldn’t help but think that Alcaraz was one of a very few players who had the privilege of wanting to lengthen rallies against Djokovic. Most are told to shorten points because Novak’s athleticism and consistency from the baseline is too hard to match. Alcaraz is one of the rare few who can match him (and beat him for power), to the point that it’s actually preferable for him to have long exchanges with Djokovic. Novak is so damn good at the serve-plus-one and return-plus-one — Alcaraz said to his box that he couldn’t beat Djokovic by playing first-strike tennis while getting his ass kicked at Roland-Garros — that if you can, rallying with him is the better option. It’s just that most of the tour doesn’t have the skills to do that successfully.

10. After breaking Alcaraz at 0-2 in the second set to get back on serve, Djokovic allowed himself a prolonged roar of celebration. Much later in the set, on a much bigger point, Djokovic won a 17-shot rally with a passing winner to give himself a set point and didn’t react at all. I’ve tried for a long time to figure out a pattern from the points Djokovic celebrates and the ones he doesn’t, and I’ve come up empty. I think this is a little part of what makes Djokovic so hard to get in a groove against. Sometimes Djokovic plays perfect tennis and doesn’t celebrate, sometimes he struggles and celebrates emphatically, and it can be difficult to tell exactly how hard Djokovic is trying and how invested he is. As an opponent, that makes it hard to know what’s coming next — is Djokovic going to hit four beautiful returns and break you easily or will he cruise and let you hold at 15?

11. A titanic 29-shot rally took place with Djokovic serving at 1-2, break point. Of the 15 shots Alcaraz hit during the exchange, 12 were backhands, the last of which drifted long. It was a clinic on how to play a big point in a neutral position from Djokovic — even if the opponent’s “weaker” side is excellent, you hit the ball there again and again and again until it cracks. You hit there with pace, angles, and spin, and anything else you can produce. Djokovic used this tactic to even greater effect in his Roland-Garros match with Alcaraz. Time and again on break point, he’d just spam the ball to Alcaraz’s backhand, which would eventually lose patience and miss. The Spaniard was much calmer in this rally and it still didn’t work out for him because Djokovic made him hit so many backhands.

12. Alcaraz went up love-30 with Djokovic serving at 2-3 by playing two impressive, purposeful points that ended with winners. When Djokovic won the next four points (two with second serves), Alcaraz successfully returning just one serve among them, I thought we might be looking at a case of a Djokovic opponent simply not being sharp enough to take advantage of their successful patches.

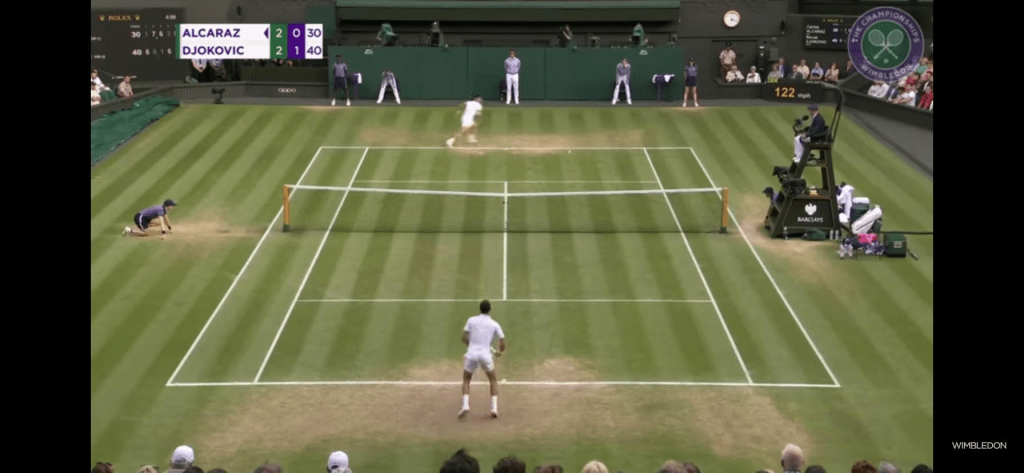

13. Some of the rallies in the second set were absurd. Djokovic and Alcaraz are the two best athletes on the ATP Tour, and they covered parts of Center Court with their incredible movement that most players wouldn’t touch in an entire career. Djokovic is the king of sliding on grass, Alcaraz is an heir apparent. That married to the remarkable speed of both produced some patterns that simply shouldn’t have been possible.

14. Watch the point Djokovic plays to hold for 5-all in the second set and tell me his defense has declined significantly from his peak. The man’s movement is remarkable. If you look at the way Nadal’s exceptional defense has declined with his injuries and age – he doesn’t slide much on hard courts anymore, and his movement off clay doesn’t compare to the wizardry he produced in his prime – Djokovic’s decline is much, much less significant. He may be ever so slightly slower, but the contortionist flexibility is still there, as is the sliding, as is a lot of the quickness. Juan José Vallejo, who has written what I consider to be the single best technical article in existence about Djokovic’s tennis, said to me on a podcast two years ago that Djokovic hadn’t lost half a step, or even a quarter of a step. I feel more or less the same right now. Djokovic has lost an eighth of a step, maybe a quarter. Not much more than that.

15. One such rally from #13 takes place with Alcaraz serving at 5-all, love-15. The young Spaniard hits a wonderful angled crosscourt backhand, like the one mentioned earlier in #4, that pushes Djokovic beyond the doubles alley. Djokovic responds with his trademark sliding backhand down the line, which he executes perfectly, forcing Alcaraz to sprint to his right instead of feasting on what should have been an advantageous position. Alcaraz’s blinding speed gets him there in time and allows him to hit a good crosscourt forehand, sending Djokovic at a dead run all the way into the other corner. Novak tries a highlight-reel forehand down the line and it just hits the top of the net tape. Go watch the rally — it’s a stunning cross-section of athleticism from the two best movers in men’s tennis.

16. I think Carlos Alcaraz has the best forehand in the world. You frequently hear people herald Stefanos Tsitsipas’s drive as the tour’s finest, but Alcaraz regularly outguns him for power – he hit 27 winners to Tsitsipas’s seven in their Barcelona match last year, for example – and, in my view, versatility. Tsitsipas’s inside-in forehand may be better, but Alcaraz returns far better with it, has the drop shot option, likely defends better from that side, and probably has more directional options. Not only can Alcaraz hit comets to any part of the court, he’s also capable of loading a slower forehand with spin and depth, as he did a few times in this match (see the point at 1-1, 15-all in the fifth set on Djokovic’s serve), crowding Djokovic for space and jamming him into a loopy, defensive shot. Alcaraz hits the forehand well on the run; just look at a few of those lasered running crosscourt passing shots from this match. Novak’s is close, but given how well he uses the forehand drop shot to mix in unpredictability to the power shots, I’d take Alcaraz’s forehand over any on tour right now.

17. I didn’t feel good about Alcaraz’s chances going into the second-set tiebreak. I felt even worse about them after he erred on a backhand down the line to open proceedings, then Djokovic predictably hit two unreturnable serves to go up 3-0.

18. As impressive as Alcaraz’s performance was — and I’ll get to that — Djokovic had a death grip on this match and let it go. It is very, very rare that he fails to close a tiebreak from 3-0 up. Besides a couple tiebreaks against Dominic Thiem at the World Tour Finals in 2019 and 2020, I struggle to think of any recent ones.

19. I would love to scrap the serve clock. Djokovic got the first and only time violation of the match at a huge moment: 4-5 in the second set tiebreak. Every time there’s a violation at a big moment, we have to listen to half of everyone watching complain that the umpire should have used their judgment, then the other half of the audience complains that rules should be applied at all times. Say all you want about attention spans, I really don’t think many people turn off a tennis match because Djokovic or Nadal is taking a few extra seconds to serve. Just leave it up to the umpire – if someone is taking an egregiously long time, warn them. If not, let the match happen.

20. Alcaraz grew considerably more comfortable at net in the second half of the match. A few times early on, he’d start to charge the net and then bail when he realized his approach shot wasn’t good enough (which stranded him in no-man’s-land and killed his chances of winning the point). At both 4-5 and 5-all in the tiebreak, he did the opposite, making a belated net charge when his forehand was better than anticipated. That screwed him as well when he couldn’t get close enough to the net and Djokovic twice passed Alcaraz with his backhand. There was little of this in the last three sets; Alcaraz made purposeful net rushes to put away easy volleys and closed down the net better so that he could produce more acrobatic volleys even when his approach shots weren’t ideal.

21. At 6-5 up in the tiebreak – set point for an insurmountable two-set lead – Djokovic netted a rally backhand. Alcaraz’s shot had been deep and took a slight bad bounce, which, though Djokovic usually makes those backhands anyway, could be a half-excuse for the unforced error. At 6-all in the tiebreak, Djokovic netted a rally backhand that was as bad a miss as I’ve ever seen from him on that wing.

Djokovic’s backhand is widely thought of as the best ever. In three tiebreaks against Roger Federer in the 2019 Wimbledon final, not only did he make no unforced errors with it (or any other shot, for that matter), he came up with a pornographic backhand winner down the line off a Federer forehand to set up championship point. To watch that same backhand crumble here, for no apparent reason, was the second-most shocking moment of the final. (For those wondering, first was Alcaraz putting himself in a position to serve out the match, then doing the damn thing.)

22. Paul Annacone once said on a podcast that he coached a player to serve-and-volley more through a set. The player thought it was a failure because they got passed all four times. “But you got two double-faults from the opponent in the tiebreak,” Annacone told them, making the point that the mere threat of the serve-and-volley produced those misses. A strategy can work indirectly. I know I wrote that Djokovic’s backhand imploded “for no apparent reason” in the last point, but I wonder if Alcaraz’s misguided net rushes put some inadvertent pressure on Djokovic’s backhand to be extra-precise. Since he’d just had to hit two great passing shots with it, maybe Djokovic felt that his backhand needed to be perfect all of a sudden, which resulted in some additional pressure or nerves that led him to miss rally shots. I can’t be sure that this is why the best backhand of all time went haywire in a huge moment, but it’s the best theory I can come up with.

23. Djokovic started the third set lethargically, going down a break (and nearly another) even before losing an astonishing 27-minute war in his 1-3 service game. He’d eventually lose the set 6-1, fully tanking the set after getting broken for the second time. Novak’s tendencies to budget his energy and focus in best-of-five are well-known. He has such extreme confidence in his abilities that he’ll let go what appear to be vital sets of vital matches, only to win the contest in the end. This is the third time he has lost a 6-1 set in a Wimbledon final, and the second time in the last four years. Djokovic won the 2011 final despite surrendering the third set to Nadal 6-1, and the 2019 final despite Federer crunching him 6-1 in the second set. He had reason to think he could tank the third against Alcaraz and still win.

That said, with the benefit of hindsight, I don’t agree with the decision. Djokovic had been ahead in 2011 and 2019 when he took a set off; in this match, the score was knotted at one set all and Djokovic willingly accepted a deficit. It cut his margin for error to paper-thin pieces. Though Djokovic nearly came back to win the match anyway, being down two sets to one meant that he couldn’t afford any major mistakes, like the swing volley he missed up break point early in the fifth set.

I’m not saying that Djokovic would have won the third set even if he’d gone pedal-to-the-metal. He might have been gassed from the brutal, hour-plus second set and needed a break to reset, in which case putting his all into the third set only to lose it probably would have resulted in a four-set loss instead of a five-set loss. But willingly falling behind against such a dangerous opponent in Alcaraz might have been too risky of a play in retrospect. Winning the third set would have been difficult; winning the fourth and fifth sets against Alcaraz was too difficult.

24. That marathon 1-3 game nicely encapsulated why Djokovic doesn’t play like a ballbasher most of the time. Usually when the Serb employs that strategy, his superb ball control allows him to make a few video-game winners, but over time the increased risk on his shots starts to tell. Though Djokovic hit a few stunning shots in this game — a missile of an inside-out forehand winner, a backhand winner down the line that found a home centimeters inside the chalk — by game’s end, he was missing forehands all over the place. Djokovic tends to ballbash when he’s seriously overmatched (he did the same thing in the second set of his four-set loss to Nadal at Roland-Garros last year, and while it worked for that set, his dip afterwards was arguably what cost him the match as Nadal remained much more consistent). Alcaraz smartly stayed steady, which eventually forced Djokovic into wild misses.

25. Alcaraz’s return performance was absolutely destructive. He limited Djokovic to a paltry 62% of points won behind the Serb’s typically imperious first serve (thanks to Jack Edward and Vansh Vermani for pointing that out on an episode of the On The Line Tennis Podcast). He broke five times (on grass!); Djokovic had only been broken three times in his previous six matches combined. When you consider that Rafael Nadal broke Djokovic seven times in Novak’s last loss in a major, it seems like the most reliable way to beat Djokovic when it counts is to win the return of serve battle. And since Djokovic is the best returner in tennis history…yeah, it’s not easy to beat him in a major.

26. Want to hear something scary? Alcaraz missed quite a few second serve returns in this match. Certainly more than he had to. He can still get better even in the areas he excels at most.

27. Everyone knew Djokovic had to make an adjustment after having the brakes beaten off him in the third set, and boy, did he make one. Already the king of taking the ball early, Djokovic relied fully on his timing and hit on the rise as much as possible – instead of hitting rally balls, he’d take the backhand early and crank a vicious angle that sent Alcaraz flying past the doubles alley. Watch the first point in the 0-1 game (which Alcaraz actually wins, thanks to some insane defense) and the last point in the 1-2 game from Djokovic: he’s just brutally running Alcaraz from side to side.

28. You can’t say enough good things about Alcaraz’s conditioning and nerve management in this match. This point has been well-documented by others, but it bears repeating here: Alcaraz’s ability to improve quickly may be his biggest asset. He understands his weaknesses, has no problems digesting defeat, and carries an intense desire to get better. Some laughed when he seriously said that he was a very different player after the Wimbledon final than he was at Roland-Garros (a mere five weeks earlier), but you know what? He was right. He made improvements on grass in two weeks that his contemporaries haven’t been able to make in two years.

29. Though Djokovic won the fourth set 6-3 (by two breaks), and pulled away at the end, Alcaraz made him work like hell for it. Djokovic had to save two break points at 0-1, then battled through a tough deuce game at 1-2. Even when he got the break at 2-all, Alcaraz saved a couple break points. Though the match was unfolding like the 2020 Australian Open final with Dominic Thiem, I noticed how much harder Djokovic was having to push to make his comeback, whereas in other matches he would start to look unstoppable even when he was still behind in the score.

30. Djokovic’s hold at 0-1 in the fourth was incredible. Alcaraz had reached 15-40 with a combination of defense that stymied Djokovic into a volley error and some fierce depth that set up his own offense. The seven-time Wimbledon champion actually looked outmatched. But he responded with a 105 mph second serve followed by a backhand down the line that was virtually a winner, then banged another huge serve. It’s a testament to Djokovic’s immense resume of great escapes that in the moment, I had expected nothing less.

31. This match was an interesting data point in terms of Djokovic’s possible decline. He’s been so dominant over the past couple years that there’s a very persuasive theory, which I believe in many respects, that Djokovic is better than he’s ever been. I think his defense has barely declined, if at all — watch his matches and you’ll still see him make belief-defying retrievals every single time. Maybe he’s not quite as quick as he was in 2015, but to me the difference is so small as to be basically negligible in the face of his improvements. The serve is far better than it used to be, the forehand has improved massively, the touch around net is sharper, and Djokovic has been more clutch the past few years than he was even in his physical prime. Overall? I’d say that’s a net positive.

But Alcaraz may have exposed in this match that Djokovic’s stamina isn’t what it was a few years ago. (The reason I say “exposed” is that Novak simply hasn’t played enough marathons recently to reliably indicate the level of his long-match fitness.) 2015 Djokovic would not have taken most of the third set off, and might even have had some extra juice for the fifth set. Decreased endurance is the main argument for Djokovic not being as good as he used to be, and even that is only apparent against the very best opponents (Alcaraz here, Nadal last year).

Djokovic faced much better competition in the 2011-2015 years than what he’s had to deal with in the past few seasons. Some of Djokovic’s late-round matches in majors have been so comfortable that it’s difficult to judge whether Djokovic is better than ever or if his competition is just sadly lacking. Still, I’d argue that at the least Djokovic is more efficient than he’s ever been, and that many of his shots are firing at all-time-highs as well. This match certainly dented the case that 2023 Djokovic is prime Novak, but for a 36-year-old? My lord, has he stayed near his best for a long time. You could make the case that he should have won this final — against someone 16 years his junior.

32. Matteo Berrettini managed to beat Alcaraz in five sets at the 2022 Australian Open, just before Carlos started winning Masters 1000s at will and rocketed into the top 10. When will be the next time someone wins a five-setter against Alcaraz? He’s the best player in the world, he’s got superb endurance, and there are no holes in his game. It could be years before he loses a deciding set at a major. Just how many is anyone’s guess.

33. Though Djokovic has the highest peak in men’s tennis, Alcaraz is right there. Djokovic went up 30-love in the first game of the fifth set and looked to be cruising to an easy hold — and then Alcaraz fired back with a forehand return winner, a delicate volley winner set up by a great backhand approach, and a backhand pass down the line. Even for all-time-greats like Federer and Nadal, it’s an extraordinarily rare occurrence for someone to produce three straight winners against Djokovic’s serve. I remember Alcaraz doing this to Djokovic at Roland-Garros as well, barreling three straight forehand winners to earn three set points at 5-4 in the second set, but I have no idea when it last happened besides these two instances. I wouldn’t be surprised if it was a few tournaments ago.

34. The break point Alcaraz saved in the fifth set was about more than just that game. Djokovic was coming on – he’d won the fourth, he had set up the break point with a classic baseline-kissing return followed by an unreturnable forehand, he had broken Alcaraz in two of his last three tries. Winning the point wouldn’t just have put Djokovic up 2-0 in the fifth set, it would have built his already-considerable momentum into an unstoppable tidal wave.

35. Djokovic’s biggest mistake on the break point was netting what should have been a putaway swing volley or overhead. But earlier in the rally, he pulled Alcaraz wide with a crosscourt forehand, and when Alcaraz sent back a hard-but-central forehand down the line, Djokovic had a look at a crosscourt backhand winner – the entire deuce court was open as Alcaraz scrambled to recover his court position. The shot would have been risky, and aiming for the line on a big point isn’t Djokovic’s style. But he played the backhand relatively passively, hitting deep but nowhere close to the sideline. Alcaraz was quick enough to get it back, and eventually Djokovic failed to put the point away. He hits that crosscourt backhand a little harder and with a better angle, maybe he’s the 2023 Wimbledon champion.

36. Alcaraz made his phenomenal defense on the break point count: he followed it up with a drop shot winner at deuce and a rocket of a running forehand winner down the line on game point. He’d never face another break point in the match.

37. Part of what makes Djokovic and Alcaraz so great is their ability to defend against superb returns of serve. I tell anyone at the club level who asks me about tennis (not many) to focus on getting returns to their opponent’s backhand; often, low-level players just don’t know what to do when they can’t follow up their serve with a forehand and their brain short-circuits. For some pro players, it’s not all that different – get the majority of returns to their weaker side, and though they won’t crumble the way a club player will, you take away their ability to attack effectively. With Djokovic and Alcaraz, the equation changes. You can hit a fantastic return and still lose the point because their incredible defense will immediately get them back into the point. (I’d say this is the most underrated key to Djokovic’s dominant serving in the late phase of his career.) On the latter point mentioned in #35, Djokovic begins by scorching a backhand return down the line that would have instantly won him the point against most. Alcaraz got there and slid into a deep sliced reply, then banged the forehand winner two shots later. Once, Kevin Anderson hit a forehand return right into the deuce corner against Djokovic, only for the Serb to clock a crosscourt backhand winner. It’s a demoralizing skill to have to play against.

38. Djokovic was getting passed cleanly almost as often as he was when he played 2006-2014 Nadal on clay. I can recall at least six separate occasions off the top of my head, some of which were on big points. (This may not sound like many, but it is given Djokovic’s style of net play — he rarely comes to net if he doesn’t have a comfortable volley, so it’s relatively uncommon to see him get passed easily.) The ultimate: after a great rally at 1-all, break point in the fifth set, Djokovic approached the net behind a mediocre inside-out forehand. Alcaraz had all the time in the world to measure his backhand down the line, which he sent flying past Djokovic before the Serb could even make a move for the ball. Credit Alcaraz’s passing shots, but also the Spaniard’s baseline prowess making Djokovic uncomfortable enough to approach the net behind such poor shots at times. If you took snapshots of some of Djokovic’s approach shots, then time-traveled to before the match and told him he’d be coming to net behind shots of that quality, he’d be wincing. But he didn’t have all that much choice in the moment.

39. On Djokovic not having much choice besides charging the net: earlier in that break point rally, he raked a crosscourt backhand that appeared to hit both the sideline and the baseline, and Alcaraz got it back. Djokovic couldn’t hit through him.

40. Djokovic demolishing his racket on the net post after getting broken in the fifth was high on the list of the dumb tantrums he’s thrown during his career. (And it’s not a short list.) There was a bit of talk at the time of the love being some kind of psychological stroke of genius, since it turned the cheers for Alcaraz’s passing shot into a wave of boos. Djokovic missing forehand returns and shaking out his wrist in the following game dispelled that idea pretty quickly. Any pain that may have been caused from the racket smash was Djokovic’s own fault, obviously.

41. Djokovic’s return pressure wasn’t exactly stifling in much of the fifth set. He had 15-30 on Alcaraz’s serve at 3-2 down and biffed a second serve return, then missed a forehand right after making a great return at 30-all. Then there was a missed second serve return at love-15 up in his next return game, and a backhand unforced error at 15-all. In hindsight, those were Djokovic’s last chances to make an impact on a big point, given how Alcaraz dictated all four points he won in the last game.

42. That said, can we appreciate the fact that Djokovic made zero unforced errors in the final game and Alcaraz held anyway? So many players get to the doorstep of finishing Djokovic off, only to lose their way when he stops missing. Federer in 2019 did exactly that. So think of what must be running through Alcaraz’s head when, after Carlos had produced a gorgeous lob winner and a filthy backhand stab volley, Djokovic returned a 130 mph serve like it’s nothing and followed it up with a forehand winner to get to 30-all. Alcaraz’s response? A service winner and an unreturnable forehand to close the show. This last game has been covered in detail (check out Igor Lazić’s article on Popcorn Tennis and Vivek Jacob’s Substack), so I won’t spend more time on it here, but if anyone ever calls Alcaraz overhyped again, sending them the YouTube clip of the game should shut them up.

43. If you ignore the 2007 Wimbledon semifinal, in which Djokovic won the first set but had to retire due to injury, Novak had never lost at Wimbledon after winning the opening set. In 2018, Nadal had break point to serve for the match on five different occasions in the fifth set, which would have broken that streak. In 2019, Federer had two match points on his serve to break the streak. And you know what? Neither of them could put Djokovic away like Alcaraz did.

44. I hope Jannik Sinner watched this match and fumed for every minute of the last four sets. Sinner was 0/6 on break points against Djokovic in their semifinal, missing rally forehands on a few of those opportunities. Is Sinner as good as Alcaraz? No. Could he have beaten Djokovic on his best day? Probably not. But Alcaraz showed what can happen when you play without fear, and most importantly execute your best shots well on big points. Sinner certainly should have pushed Djokovic harder than he did, and if he thought, that could have been me while watching his younger rival win Wimbledon, it might provide him with more motivation, which would be good for the sport.

45. It’s fascinating to predict how the Djokovic-Alcaraz rivalry will evolve from here. Usually, in a matchup with this kind of age gap, the younger player gains full control after winning an epic. But Djokovic is no ordinary rival. He leads his head-to-heads with all his remotely major rivals (Andy Roddick, who beat Djokovic five of nine times, was not a major rival) for a reason. You can bet that Djokovic will do everything in his power to figure Alcaraz out for their next meeting. We’re already thinking ahead to a possible U.S. Open final between these two. But I have to say – I’d favor Alcaraz fairly clearly in that matchup. Djokovic, for a variety of reasons, has rarely been at his best at the U.S. Open. Alcaraz has shown that Djokovic needs to be near-perfect to beat him.

46. Alcaraz has the best chance to defend the U.S. Open of any man since…Djokovic in 2012? Djokovic in 2016? No ATP player has won two consecutive titles in New York since Federer won five straight from 2004 to 2008. I’ll go ahead and say Alcaraz will be the one to bust this streak at some point, it’s just a matter of time as to when.

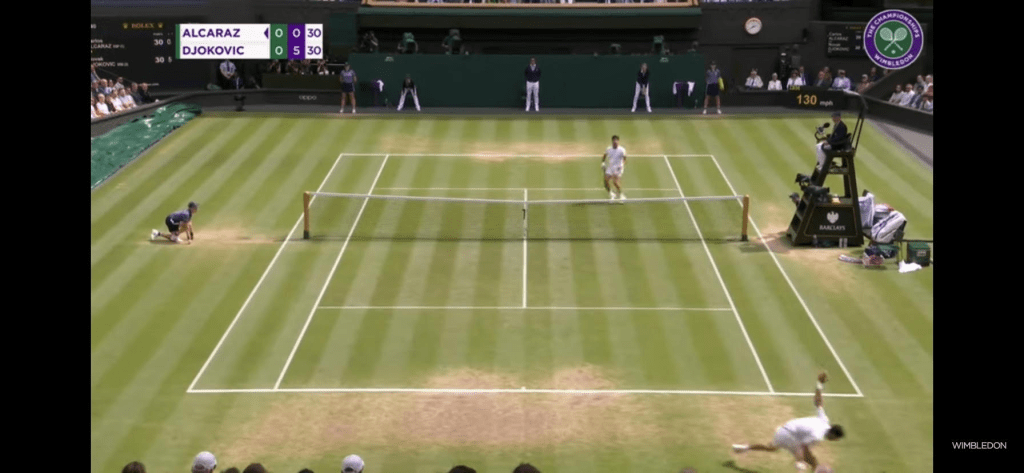

47. The amount of times the players slipped in this match — and risked serious injury while doing so — was frankly farcical. I counted five full slips to the ground for Djokovic (the best-ever mover on grass, let’s remember) and two for Alcaraz. Venus Williams, a five-time champion of the event, got injured by a slip, as did Serena two years ago. I think it’s time to have serious conversations about adapting the surface to make it less slippery. I don’t care how – use a different grass seed, use artificial grass, use whatever. At some point, a player is going to break a leg or something.

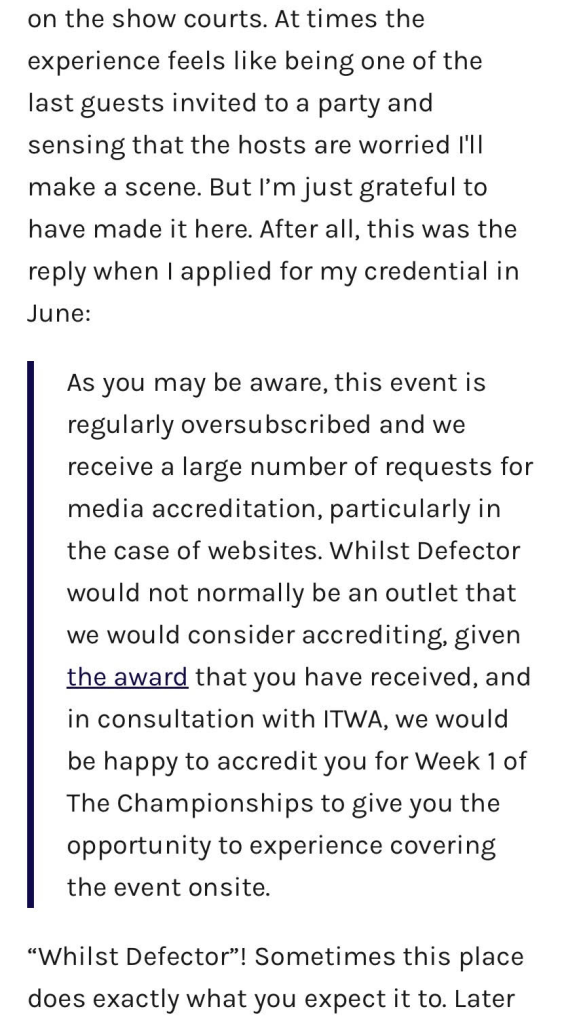

48. If you’ve gotten to this point in this article and somehow want more reading about the Wimbledon final, Giri Nathan wrote a beautiful piece for Defector. It’s also worth reading Giri’s Week One piece. Note that bit where Wimbledon turns their pretentious dial up to eleven when responding to his request for press credentials. I hate Wimbledon sometimes.

49. I don’t think this match will trigger a more significant decline in Djokovic’s tennis, but if this match is the end of his second prime, I want to take a second to highlight the enormity of what he’s achieved since mid-2018. Djokovic has won 11 majors in the past five years, all after turning 30. He has won each of the four majors at least once in that span, and three of them at least twice. He has spent a remarkable 166 weeks at #1. He beat Federer at Wimbledon in 2019 – an all-time-great mental performance – and Nadal at Roland-Garros in 2021, a legendary all-around performance (even with Nadal’s foot issues in the fourth set). It’s just a staggeringly good few years Djokovic has had. I’d wager that his post-30 career has been as good as anyone’s in any sport already, and it’s probably far from finished.

50. There’s been some debate over whether this match was really a passing of the torch given that Djokovic likely still has a lot in the tank. But it absolutely is. The player handing off the torch doesn’t need to be completely shot; Sampras won another major after losing to Federer at Wimbledon in 2001 and Federer won another eight after losing to Nadal at Wimbledon in 2008. We always thought Alcaraz was different from the endless line of very good ATP players who couldn’t beat Djokovic when it counted. After Djokovic rolled him at Roland-Garros, we wondered if even Alcaraz would just have to wait for Djokovic to retire to fully take over men’s tennis.

Now, that question has been answered: Alcaraz is capable of ruling men’s tennis, Djokovic or no. Djokovic is going to win more majors, but he’s 36; Alcaraz is 20. The Australian Open is where the 23-time major champion is at his very best, but he’s arguably been more dominant at Wimbledon in the past couple years. Taking it back to point #1, grass was thought to be the one surface where Alcaraz had next to no shot of beating Djokovic. But Alcaraz did it, breaking Djokovic’s titanic winning streak on Center Court, and is #1 in the world to boot. Novak may make successful adjustments in the matchup in the short term, but this matchup is only going to get more difficult for him as he ages and Alcaraz matures. Many in the tennis world have been waiting for a young guy to score a clear, meaningful victory over a game Djokovic for years. You won’t get a better example than this.

One thought on “50 Thoughts on Djokovic vs. Alcaraz in the 2023 Wimbledon Final”