By André Rolemberg

Whether you watch it on tv, on live, or at your local club, tennis has a unique quality among sports: it needs silence.

If you play the sport, you also notice it for yourself that any noise can break your flow, disrupt your momentum, make you downright pissed off.

Why?

Every athlete needs focus to perform. Most athletes have the super-human ability to shut off any influence from the outside world, as if nothing else existed but themselves and the game being played.

Even tennis players have that ability. Novak Djokovic spoke about the ability to cut out the crowd chanting his opponent’s name, and even magically making it sound like they were saying his instead. Djokovic is one of the most focused players ever to walk on a tennis court.

But noise still sucks. Somehow, it still messes everything up. So, if every sport needs a state of absolute focus to be performed at the highest of levels, why do tennis players need complete silence, to the point where it is a requirement if you want to watch a match live?

Here’s a few things I think could explain this rather uncommon need.

Rally structure

First of all, there is the way the rallies happen. In tennis, you are only allowed a single touch at the ball. The touch happens in a split second, meaning you cannot just land the ball on your racket and think about it: it must leave your racket nearly as soon as it touches it.

This is true for doubles as well. There is no saving grace. You mess up, and that’s it for the point. No one will be there to save it. Unlike in volleyball, a sport with some similarities, where players can produce miraculous defense and turn into attack before it even crosses the net. Or a routine play turned into nightmare if a player fails to do the job right in the first two touches: a third can still keep the point alive.

In tennis, that single touch is what you have. What’s worse: it only guarantees your survival for a little longer.

You can successfully hit the ball back 40 times in a rally. If you miss on the 41st time, you lose the point. Hitting the ball back in is the bare minimum, the prerequisite to playing tennis. Hit the ball out, your efforts are often nil.

Scoring system

The scoring system in tennis is a work of art. It is divided in a few pieces that, grossly putting, are independent of each other.

You need to score sets to win a match. You need to score games to win a set. You need to score points to win a game. You need to keep the ball in play longer than your opponent to win a point.

Conversely, you can hit 50% more balls in than your opponent, and they still finish with more points. You may win more games in a match and your opponent still wins the match. You may win more points then your opponent, and still lose the match. You may do literally everything better than your opponent, albeit just marginally, and still lose the match.

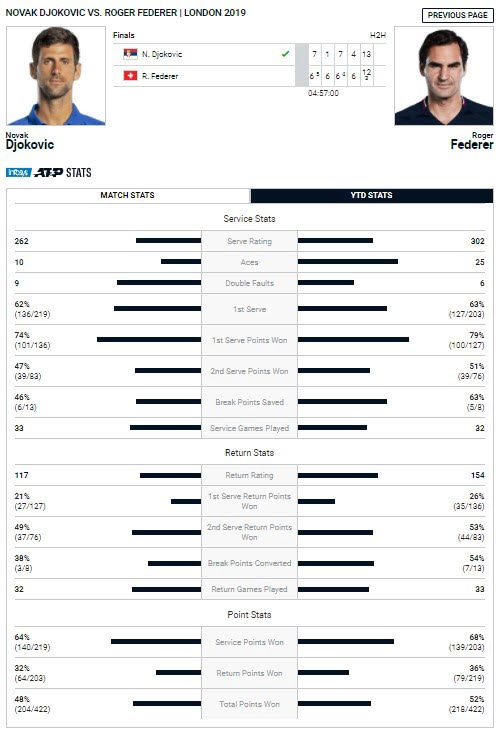

Look at these numbers — brutal. And what is worse, you must win to advance. Tennis really can be an unforgiving sport.

This brings us to pressure points: the ones that close out the clusters of a game, a set, and a match.

When a point is worth more than others, to a point where all your work can turn out completely fruitless, nerves kick in. The absolute need for precision and focus become the ultimate truth. There are no second chances. Or, at least, not after you hit your first serve.

Players need silence, because one single point gone the wrong way and it cascades down into catastrophe. A lapse in concentration, a shanked forehand, a shaky second serve, and the momentum gets pulled hard towards the other side, as if all your teammates decided to drop the rope at the same time in a game of tug-of-war.

Speed of play

Several sports are quick paced, but there’s something to be said about the incredible speeds at which balls are thrown around on a tennis court.

Not only does the ball go fast, but also racket heads move at super-human speed to generate the amounts of pace and spin we see coming from players.

With a tiny ball, rackets that have become bigger, but are still somewhat small especially if you consider that only the “sweet spot” is where you want to make contact with the ball, it makes sense to say that any distractions and it’s all over.

As previously stated, you misfire, you lose the point. Even on serve, if you lose your first serve, there goes what is possibly the biggest weapon in the game, and you have to make a choice between going for the second serve and risk losing the point with a double-fault, or playing more conservative and counting on winning the point in a rally which likely will start neutral.

When things happen fast, you have to move fast and think fast. When that happens, you cannot afford to get caught in any sort of distractions. Head in the game, or you’re off-tempo.

Technique and physics

And just as things happen fast, you must be able to do things fast, but also well. Tennis technique is very precise and also does not allow much room for sloppiness and error.

Moving well means reading the trajectory of the ball, judging the distance from your body to the contact point, placing your legs in the optimal position for optimal balance, swinging with the right distance from the racket head to your body, applying the right amount of spin or “feeling” the right trajectory of a flatter shot or a slice.

All of this happens in a fraction of a second, but obviously no one is truly thinking about these things as a step-by-step guideline when playing. It happens with muscle memory and proprioception, which is basically thinking with your body.

But, just as you can lose your train of thought if someone interrupts you mid-sentence, you can lose your balance and spatial perception if something significantly disturbs the environment you’re in.

Some sports have a higher tolerance to this. Think of soccer, basketball, hockey. They will stop at almost nothing short of a streaker or something that physically interrupts play, like an object thrown on the field/court/ice (and even still, hockey players can even play for a few seconds without a stick that has been broken, and still lies around during play.)

Tennis does not tolerate much at all. Camera flashes, people moving, a whisper too loud between people or from commentators sitting courtside.

Any small disturbance jeopardizes the outcome of a point. It could be a nuisance at 0–0 in the second game of the first set, on serve. It could be 30-all at 11–11 in the fifth set of a Wimbledon final.

The importance of a crowd

Should crowds just shut up, then?

Absolutely not. Players have *some* tolerance to a little bit of noise, and can play through “ooohh’s” and “ahhh!” sometimes. Murray did that on match point against Djokovic at his second Wimbledon final, and won. Who could blame the British crowd? It was a historical moment. Even I, who’s never been to Great Britain, felt the magic energy.

So crowds have space, and can turn things around. Think of Leylah Annie Fernandez in her US Open matches. Think of the electric atmosphere during Tiafoe-Sinner in Vienna last year (2021). Players can work the crowds. They can draw energy and adrenaline from them.

Crowds matter.

The point is, you want to be involved in the game, you want to be a part of it. What you don’t want to be is the one who breaks the flow, that swims against the current and consequently ruins everyone’s experience. Making noise at a bad time is like talking on the phone during a movie in the theatre. It doesn’t enhance the experience, it just makes you stick out like a sore thumb, and like such, anyone would want to get rid of the pain as soon as possible.

Make noise between points, scream your favourite player’s name, jump up and down.

But when the umpire says, “quiet, please”, then… Quiet. Please.