By Nick Carter

It is Wimbledon in only a matter of days and I’m so excited. In fact, I am so positive about the event, I want to share exactly why I am excited.

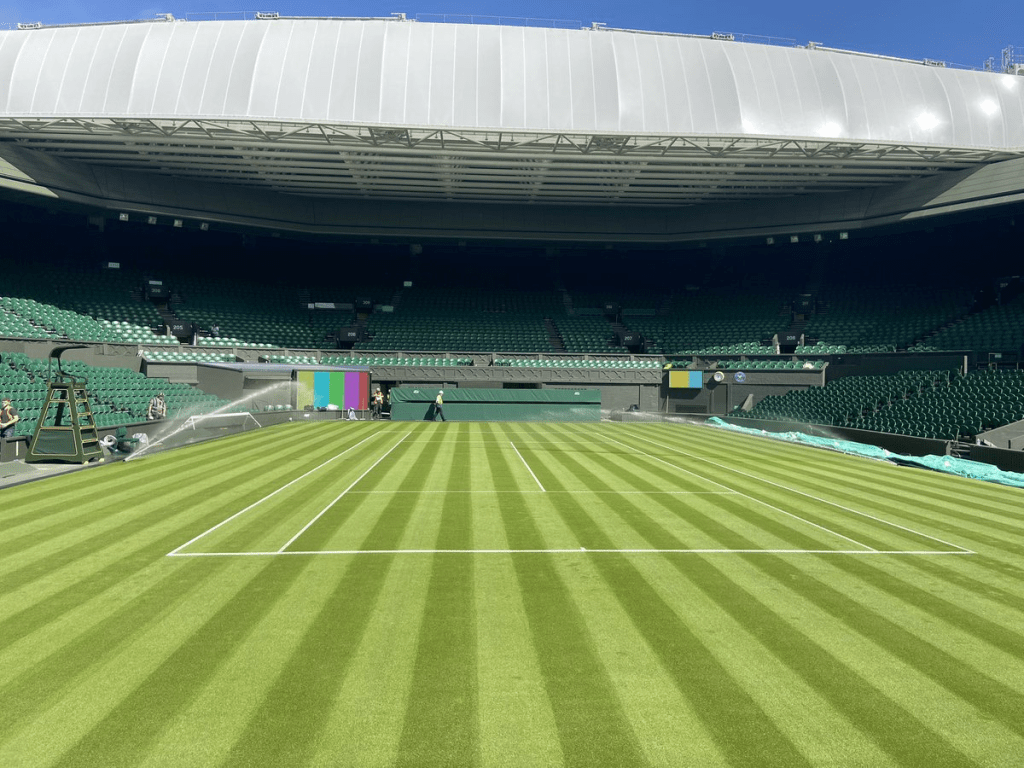

Let’s start with the emotions, and get my biases out of the way. I’m British, I grew up with Wimbledon. To me, it is the home of tennis, as for a long time it was the only event I could watch. The bright green courts on a sunny day, with two combatants clad in white playing a wonderful game that mixes power with precision and control. It is that controlled aggression that I admire the most in a tennis player, which is what appeals to me about my favourites Roger Federer and Iga Swiatek.

To me, grass court tennis is fantastic. I see too many people doing it down, comparing it to clay court tennis. Now, I like watching players on clay, the rallies are longer, more physical and technical. However, I love the fact that on grass you get more winners, and aggressive play is rewarded more often. The way players have to get down that bit lower to scoop up shots is great to watch and this adds to the power plays we see. Actually, the idea that grass court tennis is more boring doesn’t sit well with me. Yes, you get a lot more serve dominated matches but at least those are over quickly. Dull matches occur just as often on slower surfaces, but they just look different (lots of neutral rallies ending in errors). I’m not going to say different people’s tastes are wrong, what you enjoy or not is up to you. All I’m asking is that you let me enjoy tennis on grass.

In fact, I’d say Wimbledon has produced contenders for the best match of the year for the last decade and a half. Certainly, the finals are usually the best the majors have to offer. The Australian Open has usually provided the main competitions, and it takes place on a fast surface. That’s a tangent as part of my fast-court tennis agenda. If you look at men’s tennis then you can say that Wimbledon produced the definitive best match of the season in 2007, 2008, 2018 and 2019. Two of those matches were the best of the decade, if not of all time. If you look at 2009, 2014, 2015 and 2016 Wimbledon produced matches that were contenders for best of the season even if they weren’t clear winners like the previous list. Add in 2011, 2013 and 2017, which also produced some well-remembered matches, and suddenly that’s 11/14 Wimbledon events that have given us some awesome moments. That is just in the men’s game, given how the WTA has produced some consistently great battles over the last couple of years, Wimbledon should magnify this.

Furthermore, Wimbledon is where the greats truly rise to the occasion. Most winners at SW19 are multiple major champions or world number ones. In the Open Era, there have only been seven players who have won their only major at Wimbledon: Marion Bartoli, Goran Ivanisevic, Jana Novotna, Richard Krajicek, Conchita Martinez, Michael Stich and Pat Cash. Otherwise, Centre Court is the home of champions, with many of greats being dominant on finals day. Great players including Roger Federer, Serena Williams, Bjorn Borg, Pete Sampras, Steffi Graf, Martina Navratilova and Novak Djokovic have won five or more titles here. Only a few players in history who could be included in the goat debate have failed to win here (off the top of my head I’m thinking of Ken Rosewall, Ivan Lendl, Mats Wilander, Monica Seles and Justine Henin), but they usually find themselves in the final at some point. With tennis’ long history on grass, Wimbledon is the place where greatness can be best compared. Every other major has fluctuated in importance over the year, but The Championships has always been at the pinnacle.

So, that’s why I’m excited in general for Wimbledon and always will be. What about Wimbledon 2022 though? The event has come in for a lot of criticism because of recent events, which I have talked a lot about already. However, if you unconditionally love someone, how you feel about them doesn’t change even when they make mistakes. This sums up my feelings about Wimbledon right now. Regardless of how much I disagree with what they’ve done recently, I am looking forward to the action.

I’m not going to do a full preview here, I want to keep this general. However, the 2022 edition of Wimbledon, the 100th anniversary of Centre Court, already has a lot of elements that will make this specific event very interesting.

First of all, this is the first major since the 2021 Australian Open where Novak Djokovic and Rafael Nadal are the top two seeds. The last time these two played in a major final against each other was at Roland Garros in 2020. Nadal has a really tough draw, but I’m done underestimating him this year. If they were to meet in the final, Djokovic would be the favourite for what would be his 7th title (he has not lost at Wimbledon since 2017!). However, part of me would be thrilled if Nadal won his third, especially given how he’s underperformed on grass after a streak of five consecutive finals (when he played the event). Regardless, the result could really swing the grand slam race definitively one way or the other.

Other things to watch for in the men’s draw are the performances of other grass specialists. Matteo Berrettini is probably the best grass court player in the world right now outside of the “Big Four” (and yes I am including Andy Murray if he’s at his peak and fully fit). If he takes on Nadal in a semi-final, I could see him producing what would be the biggest win of his career. Berrettini is often underrated and overlooked as a player, and it’s worth reading this piece by Owen about his career. Then of course there’s Felix Auger-Aliassime (who also is potentially drawn to have a run-in with Nadal) and Hubert Hurkacz, who seem to have figured grass out better than most. It will be interesting to see how Carlos Alcaraz does. He’s had some time out so is likely to be rusty, but his game should work really well on grass thanks to his big strokes and matchplay skills. This Wimbledon will be the real test of his skill there. There are also two wide open quarter-final spots, as both Casper Ruud and Stefanos Tsitsipas do not have great reputations on grass. I think this is harsh on Tsitsipas, who has reached the fourth round at Wimbledon before and did reach the Mallorca final. Unfortunately he is in a tough section with those who have better surface records.

Moving to the women’s singles, and it feels odd to say the event feels wide open when Iga Swiatek is still on this massive winning streak. This is due to the perception of her game not being quite as effective on grass. What I would say about that is that her run last year was pretty strong until Ons Jabeur got in her head in the fourth round, and she is still a former junior champion here. There are players who will be bigger threats to her on grass though compared to hard and clay. Jabeur is the obvious choice here, and now she is world number two she has an opportunity to solidify that status. The Tunisian woman’s game is so suited to grass and she now has the experience to manage the occasion to her advantage. Former champions Simona Halep and Angelique Kerber should not be counted out either, they have a special relationship with SW19 that gives them an advantage. Last year’s runner up Karolina Pliskova should be on the list as well, although she is hard to predict, whilst former US Open champion Bianca Andreescu has built some form since her comeback and has arguably underperformed at Wimbledon. Coco Gauff should not be counted out as she seems to have unlocked some potential within herself and then there’s the amazing run of Beatriz Haddad Maia at the British warm-up events in Nottingham, Birmingham and Eastbourne. I don’t see the Brazilian as a title contender but I think we’ll see her in the second week. One more name I want to throw into the mix: Jelena Ostapenko, the 2017 Roland Garros champion and 2018 Wimbledon semi-finalist. Her grass court game is really strong and I think she is a serious contender every year.In short, I don’t think there will be any random winners, but it will be a real battle for whoever does come through (my pick is still Swiatek though).

Of course, the big story for a lot of people is the return of Serena Williams, and the big question is whether this will be her final time playing Wimbledon. I’ve given up trying to predict when the greats will wrap up their careers, and she can carry on as long as she wants. Still, if this is the end for Serena, I hope it is on her own terms and in the spectacular style we have come to expect.

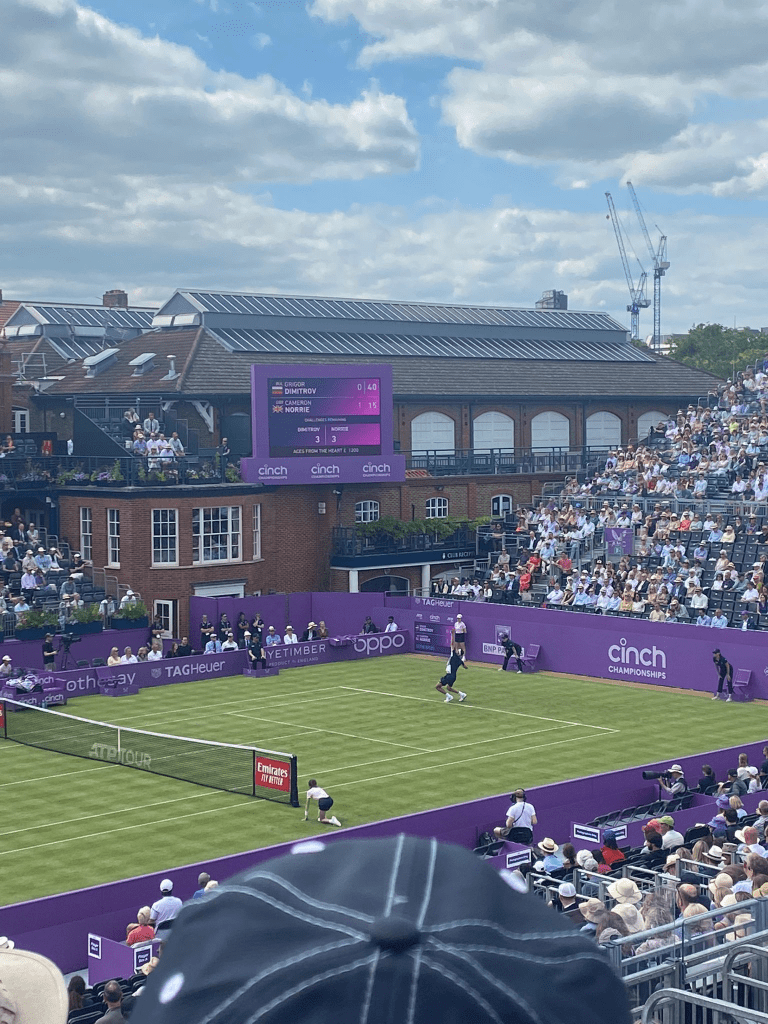

Finally, I’ll be watching the home favourites with great interest. Interestingly, it hasn’t been the British players one would expect to be making headlines who have suddenly hit form in the warm-up events. Ryan Peniston won a lot of people over after his exploits at Surbiton and especially Queen’s Club. Katie Boulter got some big wins and Harriet Dart some deep runs, whilst Jodie Burrage somehow managed to dig deep to beat a top five player in Eastbourne. Jack Draper seems to be going from strength to strength, and has a growing fanbase. All these players should have some really good momentum and provide some good news stories for the British media to promote. Cameron Norrie and Dan Evans haven’t set the grass alight these last few weeks but they’ve got decent draws so should reach round three. Then of course there is Andy Murray, who is returning after his injury sustained whilst playing against Berrettini in the Stuttgart Open final. I think if he’s fully fit, he’ll be back in the second week and challenging for a quarter-final spot. Yet again, the Scot will be the best hope for British interest at Wimbledon. In fact, Emma Raducanu is somehow the player with the lowest expectations as she’s still recovering from her own injury woes and is drawn against a very in-form Alison Van Uytvanck in round one. There is a lot of potential here for the best result from British players as a whole at Wimbledon in a very long time. I could see four still standing by Middle Sunday. As a Brit myself, this excites me greatly.

In my view, Wimbledon is awesome in general and there are reasons to look forward to it whatever the context. The story of 2022 so far means that these next two weeks could end up being the most intriguing chapter so far. And, this will be another glorious summer in my love affair with the event. We’ve had some disagreements recently, but I still hold on to what’s important, and I want it as an unconditional part of my life. So, here’s to two weeks of sunshine, tennis, nostalgia and great moments.