Note: I’ve been trying to make my tennis writing about more than tennis recently. It’s a learning process. This is a sequel of sorts to this piece.

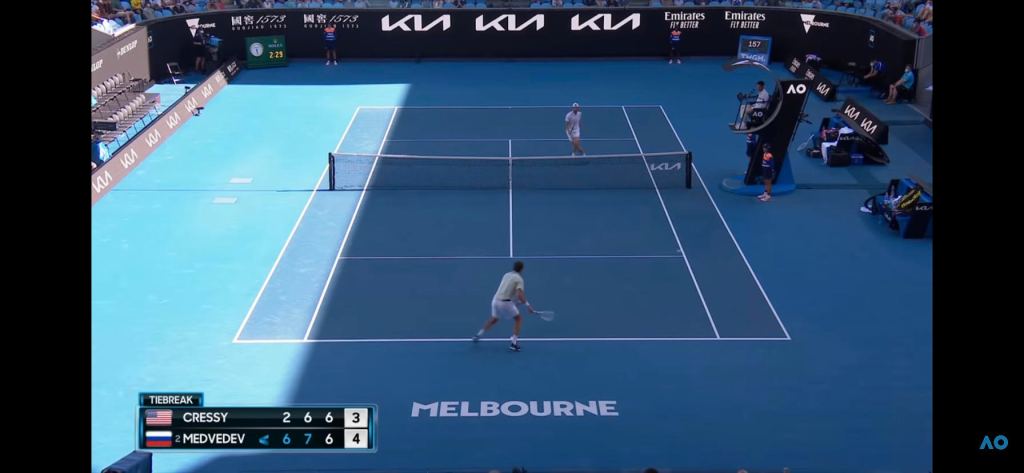

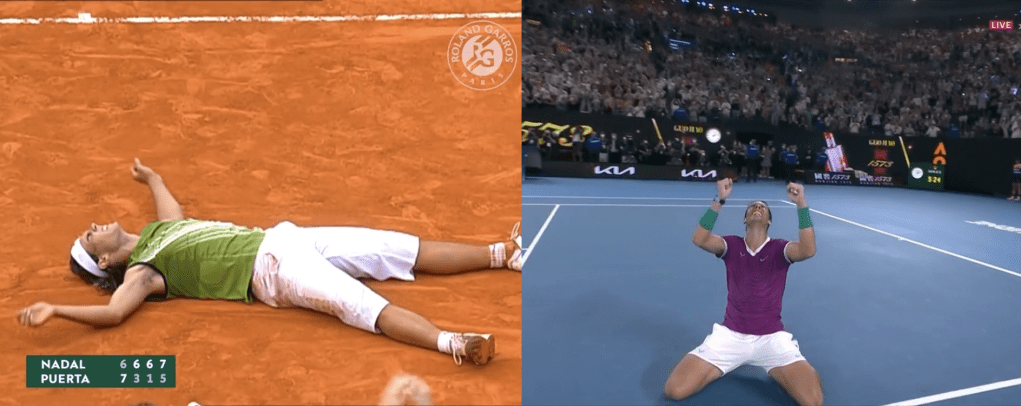

There is a difference between getting it and getting it. Five days ago, Rafael Nadal beat Daniil Medvedev from two sets down to win the Australian Open final. Medvedev got it, because he had beaten Felix Auger-Aliassime in a similar way two rounds earlier. But he didn’t get it, because he had never and has never won a major final from two sets down, or even won a close match at that stage.

Getting it is comprehending what’s going on, because you see something that makes sense. Getting it is understanding the ins and outs, because you yourself have been there.

*****

No professional tennis player has avoided a heartrending loss. Heartbreaking near-misses can be learned from, but they have to be felt. It’s impossible to learn how to climb out of the pit if you’ve never been low enough to see the bottom of its walls. It’s a process, and not an easy one — the loss hurts, sometimes so badly that it takes a while before the player is ready to climb. Take Denis Shapovalov, who lost to Djokovic in the semifinals at Wimbledon and spent the next several months floundering well below the level he was capable of playing at. Shapovalov’s loss was in straight sets, even! At this Australian Open, he made the quarterfinals, had Nadal on the ropes early in the fifth set, then folded. He was over the pain of the Wimbledon semis, maybe, but whether he learned anything from the match is yet to be seen.

Getting it is such a long, layered process that anyone not at a GOAT-level is probably a few steps away. There are so many lessons to learn in tennis. Perhaps an infinite number. There is the pressure of winning, then the pressure of backing up wins. There is the pressure of keeping your head to win the matches you’re supposed to and the pressure of preparing well enough to win the matches you aren’t. The pressure of satisfying the crowd if they like you and ignoring them if they don’t. You have to resist burnout, to tune out the media. You have to find a balance between the full-time grind of the tennis tour and your “personal life.” And that’s just the abstract stuff. The X’s and O’s of actual play are their own disaster, especially in bad matchup situations. Just ask Matteo Berrettini, Nadal’s opponent after Shapovalov. More precisely, ask his backhand.

Who out there hasn’t been absolutely leveled, at one point or another, by at least one of these challenges? Federer has choked; Serena has struggled recently in major finals. Nadal can’t stay healthy. Djokovic shoots himself in the foot time and again for a variety of reasons. And these are the lucky ones, relatively speaking. Every other active singles player has suffered exponentially more.

What must that be like? When you reach number one, it’s not even the end of the road, it’s the beginning of a new challenge: staying there. Oh, and make sure you have a major before you get to the top spot, because the media won’t let you hear the end of it if you don’t. (Condolences to Dinara Safina and Caroline Wozniacki in particular.) Tennis is a game about errors. Consistency is always difficult, but playing on wildly different surfaces against wildly different opponents while traveling all over the place makes it a near-impossibility. And yet, when a player wins a major and then fails to win the next one, they’re not surface-versatile, or they’ve lost motivation. How can a player maintain a love for tennis in this aggressive atmosphere?

The short answer is that I don’t know. When a tennis player celebrates an illustrious win like Nadal did this past weekend, I can marvel at his apparently pure joy and be happy for him, but I’m a spectator. I don’t know how it feels. (Don’t bother asking the champions, they won’t tell you.) When Novak Djokovic says that Wimbledon grass tastes like sweat and dirt but also sweet like victory, I tend to think yeah, but…sweat and dirt are gross, dude. To change the taste, you must have had to change the biological makeup of the grass with your happy emotions alone- ohhhh, wait. It’s very difficult to identify with, because while I know that he must be feeling something incredible, I have no idea what that feeling might be.

Andre Agassi’s autobiography Open offers a fairly comprehensive breakdown on how he felt after winning his first major:

"Waves of emotion continue to wash over me, relief and elation and even a kind of hysterical serenity, because I've finally earned a brief respite from the critics, especially the internal ones."

This is easier to get in touch with — I have had moments when happiness flowed through me in waves. Still, I’ve never faced the great expectations Agassi did, never had it drilled into me from toddler-age that I must be the best in the world at something. I see how he feels. I can understand why he feels that way. But I don’t get it.

This is a different phenomenon than, say, listening to a four-year-old talk about how they can’t wait for Santa Claus to come on Christmas. You know the idea of Santa Claus is bullshit, but you didn’t always, which counts for a lot. Though the knowledge you gain as you age destroys your innocence beyond hope of revival and you will never believe in Santa Claus again, you vaguely remember what it was like to believe once. You didn’t always question what you were told. “Logic” was once a funky-sounding word instead of a concept. You get the Santa illusion, even if you aren’t fooled by it anymore and can never take the glasses off. Relating to a tennis champion is way harder. I’ve never even had the privilege of dreaming about winning Wimbledon.

Even a bit of experience doesn’t necessarily teach someone what they need to know. Nadal had played in five Australian Open finals before last weekend — all kinds of matches, from getting demolished to winning narrowly to losing even more narrowly. When he couldn’t serve out the final from 5-4, 30-love in the fifth, he was so shaken by the flashbacks that he said the word “fuck” when talking about the moment on Eurosport. I was once at a running camp, and a nutritionist came to talk to us. You have to try a food at least ten times before you can be sure you like it, she said. I truthfully told her that I didn’t have that much toughness in me and jokingly asked if there was a drug I could take to suppress the gag reflex. There was not. I wasn’t being totally sarcastic — I tried mashed potatoes for the first and last time eleven years ago, spat them into the sink, and vowed never to eat them again. (I have stuck to this.) Experience can breed bad memories as easily as it can offer lessons, and gagging up mashed potatoes is very low on the anguish scale.

*****

There are so many possible permutations of how a tennis match can go, a staggering number of hurdles that can be tripped over, that it’s no wonder each tennis career is so different. Again, even the GOATs have scars carved into them by losses that would make the devil wince. A player can be proficient in one area and never master the others. What of the players who didn’t have the fortune to grow up at a slightly-to-medium tall height and weren’t born with prodigious talent? What must it be like to live on the tour knowing your game is severely limited, and that to an extent, you can never improve, just maximize the tools you already have? Reilly Opelka and Diego Schwartzman walk the earth knowing they will never lift a major title. For different reasons, sure, but how do you reconcile that with the responsibility of trying your hardest?

In the middle of the Australian Open, I wrote at length about how I felt for Adrian Mannarino. I wasn’t sure how he would cope mentally with playing some of the best tennis of his career only to get demolished by Nadal. Well, Mannarino is now playing the Open Sud de France. He just opened his title bid with two clinical straight-set wins. I can’t wrap my head around how he’s doing it. Is it love for the game that enables players to keep going like this? If so, how can that love possibly persist as the game tells the player time and again that it doesn’t love them back?

As fans, we have the privilege to watch whatever match we want, then choose to continue following the winner later in the tournament or not. The loser has to process their loss, decide what it means and whether they should care, then go back to training and try not to lose again in the same way. Even the very best players lose at more tournaments than they win. Think about it too hard and on a purely philosophical level, playing professional tennis seems like a nightmare. (For many, it’s also a financial nightmare.)

*****

At 2-all and break point in the fifth set of the Australian Open final, Nadal did one of the craziest things I’ve ever seen. He ran down a forehand down the line from Medvedev and slammed the ball back down the same line. The ball was in by an inch or so. Medvedev started walking as it blazed past him. Not to get to the ball, to walk to his chair for the changeover. It wasn’t the shot that amazed me so much; Nadal has hit that forehand hundreds of times. It was the fact that he decided to hit it. Nadal had been winning essentially every rally in the preceding minutes — if he got Medvedev’s serve back, he was winning the point the vast majority of the time. The play, very obviously, was merely to keep the ball between the lines and Medvedev would misfire or hit a sitter. Yet Nadal decided to go for one of the riskiest shots imaginable. The decision was completely bizarre to me. Why walk a tightrope when you can cross a bridge? But I’ve never been in a moment like that, I’ve only watched them. Rafa’s been there before, and for whatever reason, he decided that a Hail Mary of a forehand was the best shot to hit under the circumstances. It made no sense to me, but it did to him, and that wound up being all that mattered.

It feels important, my inability to get it. Not that it’s a failure on my part — I think anyone who hasn’t been there is in the same boat as me — but for some reason, it’s meaningful to me that I describe my detachment well. I read my favorite writers while drafting this piece — Juan José Vallejo, Louisa Thomas, Brian Phillips. I stumbled across a new one: Rembert Browne. Grantland might have been one of the best things to ever exist. I listened to “Breathing Underwater” on repeat, a song that begins with intensity, making me anticipate the chorus from the beginning. Is this my life? When I am sitting and listening and reading Rembert Browne tell a story about the Super Bowl (an event I do not care about and have not in years) well enough that I am feeling genuine suspense despite the event in question happening seven years ago, I feel, for just a moment, that I get something essential, even if I’m not sure what it might be.

The moment is not eternal. Metric, the band, tells me that I should never meet my heroes. On Sunday, Nadal served for the final at 5-4, 30-love. He got broken, then broke back immediately for 6-5. He won a long rally to go up 15-love. I started to cry. I felt the history of Nadal’s near misses in Melbourne, and how tenuous his window was to grab a second title, and all I could think was for the love of God, man, would you please serve this out?! He did. It was a nice moment. Today, he tweeted about beginning an NFT project with a company called Autograph. This is annoying because NFTs are often bad for the environment, and anything that has selling a digital Pokémon card with Logan Paul’s face on it for tens of thousands of dollars under its umbrella is just very dumb in general. Next, Nadal retweeted Autograph’s tweet, which was asking people to sign up to be the first to know about Nadal’s upcoming project. Not to take part in it, to be the first to know about it. Is this my life?

*****

Tennis is an incredibly complex game, and that word extends beyond the on-court competition. There are advantages, disadvantages, setbacks, “Get Out of Jail Free” cards. There is a starting point and a destination. Everything in between is chaos. All the participants are playing on the same board, but everything from speed of movement to direction varies wildly between those who take part. It is endlessly devoid of logic. I’m not complaining — I find the vexing nature of the sport fascinating, and stumbling upon a seemingly correct conclusion all the more rewarding for it. But it’s interesting to think that I’ve been glued to the game tennis players engage in for years now, and I get it, because I’ve been watching intently, but I don’t get it, because I’m not playing the game myself.