By Aoun Jafarey

How can you get from zero to 360?

Zero to 60? That’s what you care about for a decently fast car. Got something more serious, maybe a zero to 100 time. Supercar? 0-200 would be more apt.

But what if you have a hypercar? The kind you see once in a blue moon (unless you live in Dubai, Hong Kong… or Monte Carlo). You’d probably be interested in the top speed more than anything else. At least in the case of the McLaren F1, that was the stat that mattered the most, it became the first car to cross the 360 kmh top speed barrier by topping out at 387 kmh. Men’s tennis now has something comparable to what the auto industry had when the McLaren F1 first came out: a man who has made it to 360 weeks at number one.

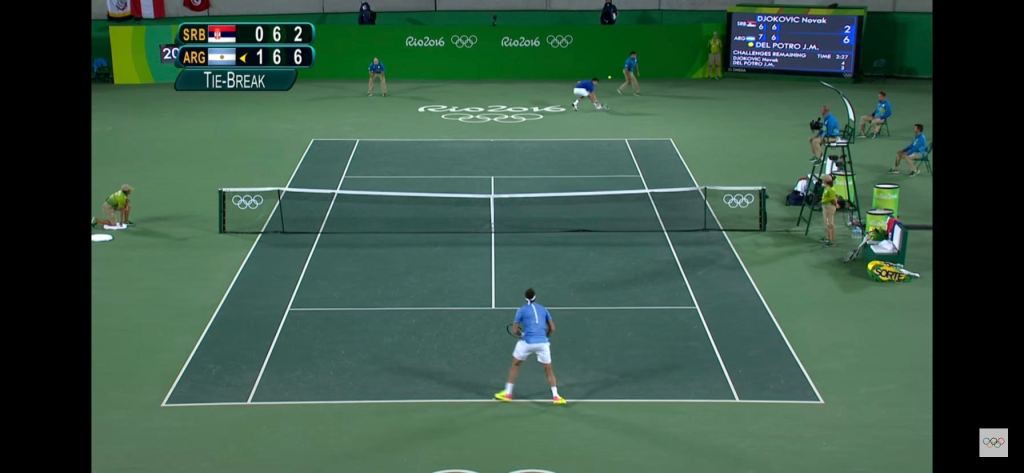

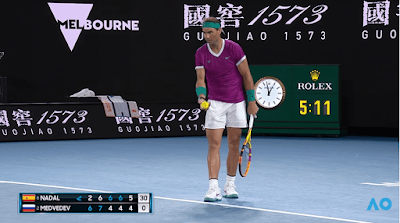

That man is none other than one of the most decorated tennis players of all time, Novak Djokovic. I know that right now media coverage of him is exploding for his opinion on vaccines and his travel to Australia, but as much as that might be consuming your timeline or newsfeed, the thing to really focus on when it comes to Novak Djokovic is his tennis.

With that cleared up (seriously, let go and let’s get back to tennis), here’s a look at some of his greatest accomplishments, some (hopefully) surprising stats in numbers, and a little jab for fun (not the literal kind before you decide to quote tweet this piece without reading the rest of it).

*****

0 – The number of COVID vaccinations he’s going to take and the number of times he’s responded to taunts from Nick Kyrgios

1 – His highest rank

2 – The number of times he has won Roland-Garros, Monte Carlo, and Cincinnati, the trifecta of his least successful “big titles”

3 – Number of games he won in his first ever match at a grand slam (R128 loss to Marat Safin) and the number of games he lost in his first ever win at a grand slam (R128 win over Robby Ginepri)

4 – The number of attempts it took for him to win a match at the Australian Open (hilarious given what happened after this)

5 – Number of times he’s won the World Tour Finals

6 – The most number of times he’s lost a final at a tournament, six each at Rome and the U.S. Open

7 – Number of times he’s finished the year end number one (most in the Open Era on the men’s side), the fewest number of games he’s ever won in a grand slam final, and the number of tournaments he is undefeated at*

*Beijing as an ATP 500 and Beijing Olympics are not considered to be the same tournament. If you have a problem with that, take it up with the ATP.

8 – Number of wins over Nadal on clay, more than a combination of any two other players

9 – The number of Australian Open titles he has won, his most at any tournament and the most by any man at the Australian Open in the Open Era

10 – The number of players who hold a winning head-to-head record over him

11 – The number of finals he has played in Rome, the most for him at any tournament

15 – The number of times he’s lost in straight sets to Nadal and Federer each

18 – The most number of wins he has over a player with 0 losses, the record is against Monfils

20 – The number of grand slam tournament titles he has won, joint for second most on the men’s side

21– The number of matches it took for him to win 10 matches

23 – The number of times he has lost to Federer

27 – The number of times he has defeated Federer

28 – The number of times he has lost to Nadal

30 – The number of times he has defeated Nadal (no other player is even at 20, Federer is second-most with 16)

31 – The number of grand slam finals he has made, joint most with Roger Federer and the number of times he has played the #1 ranked player

32 – The number of matches it took to make his first semifinal on tour (Zagreb)

37 – The number of Masters 1000 titles he has won and the number of finals he has lost on tour

49 – The number of matches he has lost to players from Spain (the most from an individual country)

50 – The gap between him and Federer for weeks at number one

51 – The number of matches it took to make his first quarterfinal at a grand slam tournament (Roland-Garros)

54 – The number of Masters 1000 finals he has played

57 – The number of countries he has played different players from and also the number of wins combined over Nadal and Federer

62 – The number of matches it took to make his first final and get his first title on tour (Amersfoort)

72 – The number of wins he has over players from the United States

78 – The number of players he has lost at least one match to

79 – The number of match wins he has at Wimbledon

82 – The number of singles matches he has won (including opposition retirements) at each of the Australian Open, Roland Garros, and the U.S. Open. Talk about symmetry.

86 – The number of titles he has won on the pro tour

89 – The number of matches he’s played at Wimbledon

90 – The number of matches he’s played at the Australian Open

91 – The number of finals he has won (including his personal match wins at team events like ATP Cup and Davis Cup)

95 – The number of matches he’s played at the U.S. Open

97 – The number of matches he’s played at Roland-Garros

102 – The number of singles matches won on grass, tied with Pete Sampras

103 – The number of sets he’s won in his 199 losses

104 – The number of matches he’s lost to players ranked in the top ten

106 – The number of matches he’s lost in straight sets

116 – The number of wins he has over players from France

123 – The number of singles finals he has contested on the pro tour

131 – The number of wins he has over players from Spain

144 – The number of indoor matches he’s won in his career

157 – The number of matches it took to make his first final at a grand slam tournament

174 – The number of times he’s made it to the SF of a tournament

182 – The number of top five ranked opponents he has played, the most amongst any man in the Open Era

187 – The number of indoor matches he’s played in his career

198 – The number of times he’s made it to the quarterfinal of a tournament

199 – The number of professional singles matches he’s lost

200 – The number of players he has played and never lost to

234 – The number of matches he’s played against an opponent with an ELO rating of at least 2200, the most of any male player

248 – The number of singles matches he’s won on clay, three more than McEnroe and Becker combined

268 – The number of players he holds a winning record over H2H

271 – The number of players he has defeated

278 – The number of sets lost in grand slam matches

319 – The lowest ranked player he has ever lost to, Filip Krajinović (it was a retirement, but it counts)

325 – The number of singles match wins at grand slam tournaments

335 – The number of top 10 ranked opponents he has played, the second most, only eclipsed by Roger Federer who has played 352 (in case you were wondering)

360 – The number of weeks he’s been ranked number one in the world by the ATP, standalone record

*****

Next week, Djokovic will finally be back to the kind of court we’ve all grown used to seeing him on, a tennis court. It’s been a long wait, and while you can disagree with his politics and opinions, you cannot disagree with the fact that he’s been a pivotal contributor to the game and one of the greatest athletes you will ever see across any sport. Let’s focus on that instead. Congratulations on an illustrious career to date, Mr. Djokovic, along with making it to 360 weeks as the world number one, a record that might outlive most of us reading. Looking forward to your tennis in Dubai.

Also, thank you to Ultimate Tennis Statistics (www.ultimatetennisstatistics.com) for providing match by match data with scores.