By Damian Kust

Between Wednesday and Sunday of the second week of the Australian Open, a total of fifteen finals were contested. Eight of the fifteen were played on Rod Laver Arena, with both the boys’ and girls’ doubles getting the second biggest stadium at Melbourne Park, Margaret Court Arena. All but one of the six wheelchair finals were played on Court No. 8 as Australian hero Dylan Alcott got the chance to finish his career on RLA. Here are my thoughts on all of them, in chronological order.

Wednesday

Wheelchair Women’s Doubles

Diede de Groot/Aniek van Koot – Yui Kamiji/Lucy Shuker 7-5 3-6 10-2

Started around 1:30 pm Melbourne time

Court No. 8

I had absolutely no idea what to expect coming into this one. I had watched some wheelchair matches in the past but I do believe they were exclusively singles and probably mostly men’s. Diede de Groot was a name I was very familiar with as she grabbed a singles Golden Slam last year, but without googling I wouldn’t even know which one of the Dutchwomen she was. I looked it up but only after a while, which was a conscious effort to stay unbiased in my understanding of the final.

About an hour into the match, I wasn’t surprised to learn that the best player on the court was in fact de Groot. There was a clear power difference between her and the other competitors, although her partner, Aniek van Koot, possesses a very pleasing forehand stroke as well, albeit a little loopier.

33% of the rallies in the final went over nine shots, which included a stunning 62-shot point in the middle of the second set. With very little netplay, it wasn’t quite like the doubles I’m used to, but still made for a very fun viewing experience. Yui Kamiji and Lucy Shuker took a rather defensive approach and almost made it work, blowing a 5-3 lead in the first set before ultimately taking it to a deciding tie-break.

De Groot grabbed her 13th doubles Grand Slam title, 9th with van Koot (this is probably a good moment to remind you that wheelchair and quad doubles at Grand Slam events have four-team draws, so the first round is a semifinal). Her partner has been on the stage for a little longer and locked up her 20th. It was a pleasant way to kick off my quest and made me very excited for the upcoming women’s wheelchair singles final championship match, between, you guessed it, de Groot and van Koot.

Wheelchair Men’s Doubles

Alfie Hewett/Gordon Reid – Gustavo Fernandez/Shingo Kunieda 6-2 4-6 10-7

Started about 4:05 pm Melbourne time

Court No. 8

When people ask me who the GOAT is, I always reply Shingo Kunieda (although the more realistic version of that answer is probably Esther Vergeer, but I didn’t get to watch her play and I’m recency biased). The Japanese legend hasn’t won a wheelchair doubles Grand Slam title in almost three years though and it’s largely due to what these two Brits have been doing.

This exact final happened four times in the past nine slams with Alfie Hewett and Gordon Reid prevailing every single time. In fact, the pair has won nine straight Grand Slam events and it was easy to see why. Compared to their opponents, they positioned themselves very aggressively on the court and even utilized the net quite a bit, though with mixed results (I think on a wheelchair it’s very tough to retreat to the baseline, you’re also really vulnerable to lobs). The big difference was the quality of returning, though. Hewett in particular would just tee off on the opponent’s second serves, many times going for the instant winner.

The Brits did lose the plot for quite a bit, dropping the next four games from 4-2 up in the second. The deciding tie-break essentially consisted of two parts as it started raining and at 5-4 the players had to walk off the court. They came back an hour later with the top seeds winning 5 of the next 8 points to clinch their 9th straight Grand Slam championship. The match point was converted with yet another return winner from Hewett. As I knew that the singles final would feature him and Kunieda, I was very intrigued to see if that shot would make the same impact in the other discipline as well.

Quad Wheelchair Doubles

Andy Lapthorne/David Wagner – Sam Schroder/Niels Vink 2-6 6-4 10-7

Started about 7:10 pm Melbourne time

Court No. 8

I already stated that I had very little experience watching wheelchair doubles and I knew even less about quad, only having caught some Dylan Alcott matches in the past. I’ll get to the Australian in another section, but he didn’t make the championship match here, leaving me again with a completely clean slate of expectations regarding the players.

Fundamentally, quad doubles turned out to be a very similar viewing experience to wheelchair, even though the disabilities are naturally completely different and some players need to have their rackets taped to their hands. After the first set, I reckoned this would be the most lopsided final of the day. Sam Schroder and Niels Vink hit plenty of winners, especially going down the middle and confusing their opponents as to who should try to get the ball back. The Dutchmen played their shots with a lot more pace and it helped them dominate the short rallies (19-9 in the opener).

The match soon started turning around, and not discounting Andy Lapthorne’s impact, there was one clear MVP in my book. 47-year-old David Wagner really had that veteran quality to him and shocked me multiple times with his reactions at the net. The American actually went there quite frequently and was astonishing both at anticipating the passing shots, but also killing the point with a drop volley, even with the ball at an unpleasant height below the net. How does he do that with his racket taped to his hand?

The volleying sensei showed up again in the deciding tie-breaker, winning a crucial point with another quick and accurate reaction. On top of that, the Dutchmen seemed to have let the occasion get to them and committed some uncharacteristic unforced errors. The match ended with Sam Schroder missing a few shots that were simply intended to transfer the ball to the other side of the court, not even to achieve anything proactive.

Thursday

Wheelchair Women’s Singles

Diede de Groot – Aniek van Koot 6-1 6-1

Started around 11 am Melbourne time

Court No. 8

Diede de Groot’s last singles loss at a Grand Slam came back at the 2020 French Open (to Momoko Ohtani) as the Dutchwoman reeled off four straight titles (and the Olympics in the meantime). Van Koot’s appearance in the singles final was a minor surprise, given the 31-year-old hadn’t done it in two years and eliminated de Groot’s biggest rival, Yui Kamiji.

Having watched the doubles final on Wednesday where de Groot seemed like the best player on the court, I wasn’t surprised to see her put up a very comprehensive display and dominate the proceedings from the very beginning. Singles’ wheelchair matches turned out to be a lot more like the singles that we know, focused on 0-4 rallies and staying close to the baseline to take the ball early. Just 5% (5/97) of the points were extended over nine shots.

What decided the match was de Groot’s incredible dominance in short rallies (48-26), which came as a result of both her aggressive shots, but also van Koot missing quite a bit of the first rally balls. The 25-year-old won her fifth consecutive Grand Slam singles title and from the two matches of her that I watched, she looks like she could stay very dominant in the sport for years to come.

Wheelchair Men’s Singles

Shingo Kunieda – Alfie Hewett 7-5 3-6 6-2

Started around 12:35 pm Melbourne time

Court No. 8

Similar to the women’s wheelchair singles, this one was also far more about being the first to strike in the rally than what I saw during the doubles. I paid a lot of attention to Hewett’s returning strategy in his match against Gustavo Fernandez and Shingo Kunieda, but it turned out that in singles, the Japanese would be just as aggressive on that shot, taking it extremely early. The two combined for 27 return winners throughout the match.

9% of the rallies went over nine shots (15/173) as both players were keen on looking for winners and easy ways to win the points. Perhaps it was due to the nature of moving on a wheelchair, but many of the strokes that ended the rallies seemed to be more about the wide angle rather than being deep into the court. Kunieda finished the match with 50 winners, Hewett not that far behind with 37.

So, how did Kunieda win his 26th Grand Slam singles title (and that’s despite never winning Wimbledon, which has only been organizing a men’s singles wheelchair event since 2016)? Hewett managed to level the match but boy did the Japanese step up for the deciding set. His backhand produced a number of breathtaking winners to go two breaks up and while in wheelchair tennis, serving isn’t nearly as important (with how these guys were returning it could even be viewed as a disadvantage, 13 breaks in the whole match), Kunieda served it out for his 11th Australian Open singles trophy (1st back in 2007).

Quad Wheelchair Singles

Sam Schroder – Dylan Alcott 7-5 6-0

Rod Laver Arena

Started around 5 pm Melbourne time

One of the very rare occasions when the attention of the whole tennis world was at quad wheelchair tennis. Dylan Alcott announced before the Australian Open that he would be finishing his professional career with this event and for his last match ever, he got nominated to play at Rod Laver Arena (by the way, it would be very cool if other wheelchair finals were also on stadium courts, not necessarily the biggest one, but there’s no need to have them on Court No. 8).

This was a send-off for a very special player. A paralympic Gold medalist in both basketball and tennis, one of the three Golden Slam winners ever (along with Steffi Graf and the aforementioned Diede de Groot), winner of 15 out of 19 singles Majors he ever entered before this year. He also took seven consecutive Australian Open crowns, losing in Melbourne just once back in 2014.

But it wasn’t meant to be this time around. I mentioned Sam Schroder’s lacking mental performance in the doubles’ final, but he was extremely sharp this time around, first not allowing Alcott to serve out the opening set and then saving four crucial breakpoints at 5-5.

The momentum shift was too much as the Dutchman reeled off nine games in a row to take the championship. He exacted revenge on his opponent, who defeated him in four of the five Major finals of 2021. Alcott’s all-court style clashed with the Dutchman’s more conservative approach but the shotmaking of Schroder, especially on the backhand side, was pretty incredible.

Friday

Mixed Doubles

Kristina Mladenovic/Ivan Dodig – Jaimee Fourlis/Jason Kubler 6-3 6-4

Rod Laver Arena

Started around 12:15 pm Melbourne time

We’re entering some more familiar territory as I usually try to watch at least the final of a mixed doubles Grand Slam. Naturally, I had seen the four competitors play before, so there weren’t going to be any surprises. Ivan Dodig and Kristina Mladenovic had won Majors in mixed doubles before, but it was their first event together. The partnership clicked though and you could see why as they expertly dealt with any situations at the net, always knowing how to find an answer.

Jaimee Fourlis and Jason Kubler (also playing with each other for the first time) saved seven match points on the way to the final (4 against Sam Stosur and Matthew Ebden, 2 vs Nina Stojanovic and Mate Pavic, 1 over Lucie Hradecka and Gonzalo Escobar). The Aussie pair were impossible to put away and made their first Grand Slam final.

While Fourlis never managed to hold serve in the entire match (0/4), she certainly wasn’t a weak link of the Aussie team. Her lobs dealt a lot of damage to Dodig and Mladenovic, often catching them off-guard. The Frenchwoman won the Australian Open eight years earlier with Daniel Nestor and was able to secure the championship again after a fantastic match point, where both she and Dodig showed some great reactions at the net.

Girls’ Doubles

Clervie Ngounoue/Diana Shnaider – Kayla Cross/Victoria Mboko 6-4 6-3

Margaret Court Arena

Started around 4:25 pm Melbourne time

I usually watch some of the juniors’ tournament at the slams, but in almost all the cases it’s singles, not doubles. I was unpleasantly surprised to discover that they just play a deciding point at deuce here, which feels a bit degrading in my opinion and while it shortens the matches a bit, is it really needed with junior events starting pretty much during the second week and so many courts at Melbourne Park available? I can live with it in mixed, since then it creates the rule that at deciding points you gotta serve at the opponent of your gender, which makes sense to me.

The Canadians went up 4-2 in the opening set, showing some great instincts at the net. It was clear though that Ngounoue and Shnaider were much stronger physically and would be able to come out on top if the match drifted into a more baseline rallying style. That’s when Cross and Mboko started committing more errors on the first ball though, some untimely double faults also kicked in. The top seeds still had to play very well to take advantage and reeled off seven straight games to go up 6-4 3-0.

Cross and Mboko had a little fightback but despite pulling it back to 3-3, they were still overwhelmed in the short rallies (34-46), almost half of the opponents’ points (22) coming from their own unforced errors. The whole affair lasted just 56 minutes, which nicely ties it to my point about no real harm in playing regular deuce games here, especially as the third set would have been a deciding tie-break anyway. Diana Shnaider was the only player on the court who had already won a junior Grand Slam (at last year’s Wimbledon with Kristina Dmitruk). Ngounoue and Mboko’s performances are even more impressive when you consider that the two are just 15 years of age.

Boys’ Doubles

Bruno Kuzuhara/Coleman Wong – Alex Michelsen/Adolfo Daniel Vallejo 6-3 7-6

Margaret Court Arena

Started around 5:50 pm Melbourne time

Despite the American-Paraguayan pair being taller and therefore having a lot more reach, it was Coleman Wong’s fantastic reactive volley (which just clipped the baseline) that gave the second seeds a 3-1 lead in the opening set. Deciding points were key again and while I don’t mind them in tour-level events, my view is that a Grand Slam final probably deserves better. Vallejo managed to fend off another break point chance at 2-5 down with a great lob, but Kuzuhara’s prowess at covering the net was enough to clinch the next one, a deciding point again, this time on their serve.

Kuzuhara pulled off an incredible sprint at 1-1 in the second set, having to be very careful not to bump into the ball boys after a net cord went really wide. Vallejo’s 2nd serve remained an issue as both Wong and Kuzuhara were capable of jumping onto it and taking control of the point. The second seeds seemed to be cruising towards the finish line but in a match pretty much resolved through deciding points until that game, Michelson and Vallejo managed to break Wong as the former landed a beautiful forehand return winner.

It turned out they were only delaying the inevitable though. In the second set tie-break, Kuzuhara won a few key cross-court inside-out forehand rallies against Michelson’s backhand with Wong waiting for the right ball to poach at the net. The second seeds took it seven points to three. If I had to pick a player I was most excited to watch again it would be Kuzuhara, which left me thrilled for the boys’ singles final on Saturday, in which he’d also be participating.

Saturday

Girls’ Singles

Petra Marcinko – Sofia Costoulas 7-5 6-1

Rod Laver Arena

Started around 12:10 pm Melbourne time

A battle of two 16-year-olds, which while a little high on the error count maintained some great quality. It was disappointing to see barely any crowd on Rod Laver Arena on Saturday afternoon, which would have made it an even bigger deal for the competitors. Petra Marcinko is the current Junior World No. 1 who already owns a win over Kurumi Nara, while Sofia Costoulas making the final was not a huge surprise either. The Belgian was seeded eighth for the tournament and made some impact in professional tennis already, reaching three ITF 15K finals last year.

Marcinko’s ability to step into the court and take the ball early saw her dominate the early proceedings, but Costoulas soon fought back to keep the opening set competitive. The easy power the World No. 1 generates was a bit too much though, especially combined with the Belgian’s wild forehand (15 unforced errors off that wing).

The top seed claimed the tight opening set and managed to take it up a notch in the remainder of the match, hitting 11 winners in seven games of set 2, the same amount as in the 12 games of the opener. In spite of her attacking style, Marcinko actually dominated the extended rallies section the most (18-6 in points that went over nine shots).

Boys’ Singles

Bruno Kuzuhara – Jakub Mensik 7-6 6-7 7-5

Rod Laver Arena

Started around 2 pm Melbourne time

What a final this was – 3 hours and 43 minutes of an absolutely grueling physical battle. Bruno Kuzuhara thrived in it with his court coverage and incredible fitness. Perhaps the year of difference between him and Jakub Mensik was very important here as the Czech started struggling with heavy cramping late in the deciding set. At 15-30 in the last game, Mensik won a 33-shot rally after which he fell on the ground and couldn’t even get up to serve for a while. The brilliant final ended with two consecutive double faults as he was too hurt to even put it into the court anymore.

As it often happens in junior Grand Slams, it’s actually the runner-up that seems to be the more exciting prospect for the future. Mensik could fit in well with the trend of tall counterpunchers and has a great backhand that reminds me a bit of Hubert Hurkacz, his whole posture and movement in defense is quite similar to the Pole too. His serve can certainly be raised to a higher standard, he’s got the right physicality for this.

Meanwhile, Kuzuhara is more or less developed as a player already and while his serve is surprisingly good for his height, it’s always going to be an uphill battle to some extent due to how tennis looks today. Nonetheless, a title like this is a great way to propel himself into the tough journey that the transition to the pros can turn out to be. After the heartbreaking finish, Mensik couldn’t even attend the trophy ceremony and was taken off the court in a wheelchair.

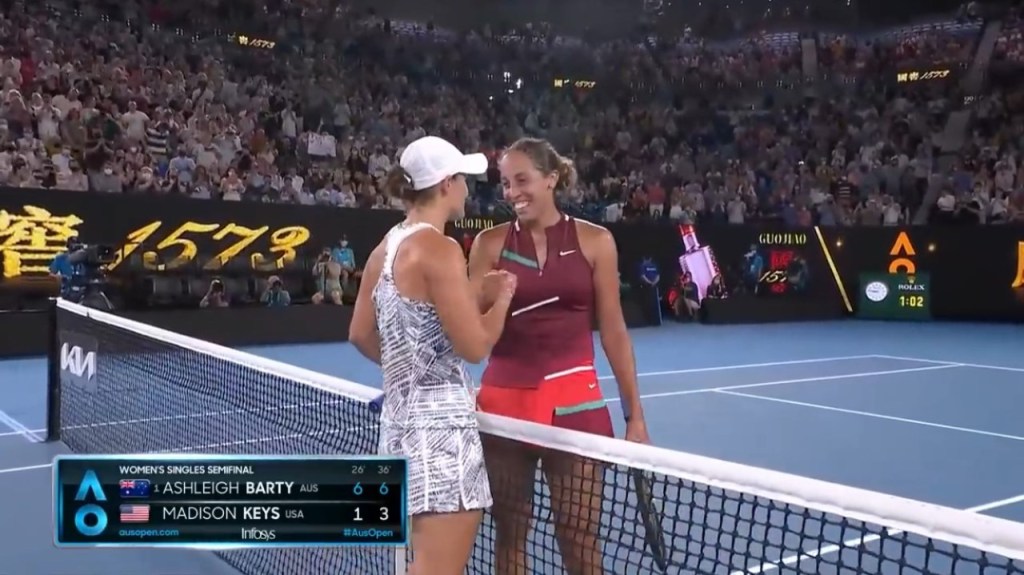

Women’s Singles

Ashleigh Barty – Danielle Collins 6-3 7-6

Rod Laver Arena

Started around 7:45 pm Melbourne time

Ashleigh Barty went through the tournament in extremely dominant fashion, dropping just 21 games on the way to the final. The Australian had her issues with pressure at Melbourne Park in the past though, throwing in lackluster performances against Sofia Kenin (two years ago) and Karolina Muchova (one year ago). Despite the home crowd advantage, it had been easier for her to maintain focus at Roland Garros and Wimbledon, even during the finals.

While the Australian started off the match in amazing fashion, mixing up spins and barely losing points on first serve, you could see some tension in how she was moving and hitting her forehand. Danielle Collins grew more confident as the 2nd set progressed and was hitting through Barty’s backhand slice with ease, utilizing her wrist action very well. She was the third player to break the Australian in 2022 as the World No. 1 earlier held 85 of her previous 86 service games.

But the difference was that Barty was able to recover this time, playing a lot more freely to get back from a 1-5 deficit in the second set. She then impressed with a clinical tie-break to clinch the championship, further solidifying her status as an all-time great. The US Open is now the only Grand Slam missing from her resume and she’s got a great chance to maintain the No. 1 position in the WTA rankings for a long while.

Mens’ Doubles

Thanasi Kokkinakis/Nick Kyrgios – Matthew Ebden/Max Purcell 7-5 6-4

Rod Laver Arena

Started around 10:05 pm Melbourne time

Was that a great fortnight for doubles as a discipline? Never before this many people tuned into it, but in a way, the message that’s going out is that singles players with good chemistry can just smash their way through elite doubles pairs. Regardless of your perspective, Nick Kyrgios and Thanasi Kokkinakis played absolutely phenomenal tennis at Melbourne Park this year.

The pair combined for 95 aces through six matches and only got broken six times, but what was most impressive was the set of opponents they managed to take out. Despite barely playing doubles in recent times, they eliminated seeds #1 (Nikola Mektic/Mate Pavic), #3 (Marcel Granollers/Horacio Zeballos), #6 (Tim Puetz/Michael Venus), and #15 (Ariel Behar/Gonzalo Escobar), feeding off the energy of the crowd. It was the first all-Australian men’s doubles final since the year 1980 at the Australian Open, although Kokkinakis and Kyrgios completely stole all the media attention. Matthew Ebden and Max Purcell also took out four seeded teams but were never going to be cheered for as much as their more famous colleagues.

The championship match once again saw Kokkinakis and Kyrgios thrive on serve and while they only managed six aces this time around, only two of their games went to deuce as Ebden/Purcell weren’t able to create any break point opportunities. The former had some issues with his volleying, while Kokkinakis definitely made their lives harder with his whippy forehand passes, always managing to keep the ball low over the net.

Two singlists coming out of nowhere to win a doubles Grand Slam is a story that hasn’t really happened in recent times, even pairs like Pospisil/Sock (Wimbledon 2014) had a lot more experience, while not necessarily with each other.

Sunday

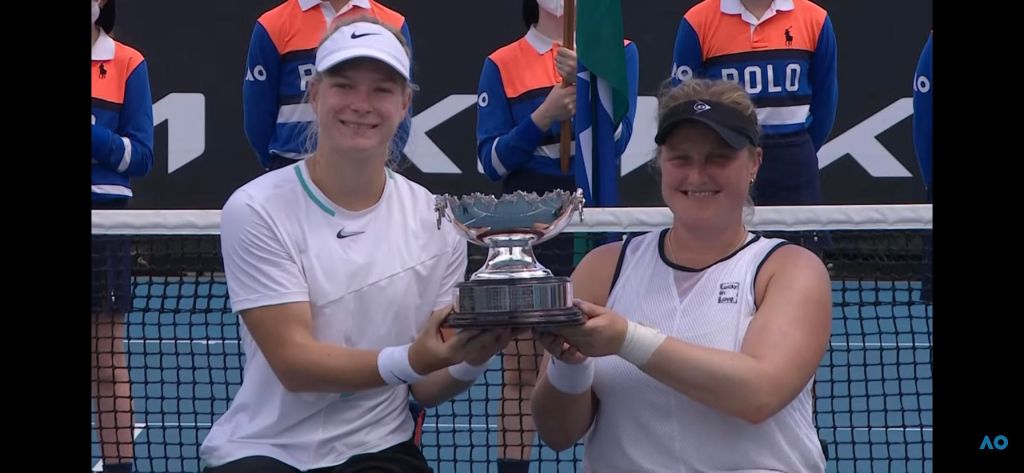

Women’s Doubles

Katerina Siniakova/Barbora Krejcikova – Anna Danilina/Beatriz Haddad Maia 6-7 6-4 6-4

Rod Laver Arena

Started around 3:10 pm Melbourne time

Top-seeded Katerina Siniakova and Barbora Krejcikova were massively favored to win this one, having already clinched three Grand Slam doubles titles together (French Open 2018, 2021, Wimbledon 2018). The Czechs faced Anna Danilina and Beatriz Haddad Maia, a new pairing who partnered for the very first time in Sydney prior to the Australian Open.

The underdogs won that warm-up event, therefore arriving in the final unbeaten in nine matches to start the year. Danilina and Haddad Maia had to win the deciding set in four of their five clashes before the final at the Australian Open, impressing in a semifinal victory over 2nd seeded Shuko Aoyama/Ena Shibahara. Krejcikova and Siniakova were yet to drop a set.

Danilina and Haddad Maia definitely had no inferiority complex here and gave the three-time Grand Slam champions a very tough time. Especially the Brazilian held up beautifully from the ground in the opening set, coming up with a clutch backhand winner to avoid giving the Czechs a set point. The lower-ranked team opened up a 6-0 lead in the tie-break with Haddad Maia eventually closing it out with a brilliant second serve for 7-3.

The favorites were visibly tense but really cleaned up their game in the next two sets. It remained competitive (total points won just 110-107 for the Czechs), but were able to regain control by dominating their own service games. It wasn’t until 5-2 in the decider that they would get broken again. It wouldn’t matter in the grand scheme of things though with Krejcikova serving out the match after a hilarious moonballing rally that neither she nor Danilina had an idea to break away from, until the Kazakh misjudged a very high ball by the and let it clip the baseline.

Men’s Singles

Rafael Nadal 2-6 6-7 6-4 6-4 7-5

Rod Laver Arena

Started around 7:45 pm Melbourne time

That was something. History was made in Melbourne Park as the 35-year-old Rafael Nadal came back to the sport after having to finish his 2021 campaign in August. Struggling with a chronic foot injury, the Spaniard wasn’t even sure he was going to be able to continue his tennis journey. But not only did he get a Double Career Grand Slam at the Australian Open, he’s also now in the lead over Novak Djokovic and Roger Federer in Major titles (for the very first time).

The expectations for the final were clear – the longer it goes, the more physical the rallies get, advantage Daniil Medvedev. That’s exactly what we got, but only for two sets and a half. Nadal did what he does best – fought like a lion and never gave up. Soon enough, in the fourth set, it turned out that it’s actually the Russian who’s got very little energy left. At one point, Medvedev was only scoring with big serves, nothing else.

The fifth set turned out to be just pure madness. Medvedev regained some energy, was once again able to keep up with Nadal in the rallies and even break with the Spaniard serving for the match. But the soon-to-be 21-time Grand Slam champion wasn’t the weak version of himself from the opening sets anymore. His backhand down-the-line became a major weapon and with well-executed drop shots, he was able to keep tiring Medvedev and move him all over the court.

What at one point looked like an inevitable straight-set loss, turned out to be perhaps his greatest ever win. Not in terms of the playing quality, but the sheer unbelievability of the fact he was even in the final to begin with, then coming back from two sets to love down for the first time in fourteen years. A historic day that we’ll be talking about for years to come.

Wrapping up

The best final of the bunch? One of the ones in contention is surely Bruno Kuzuhara beating Jakub Mensik in the boys’ singles, outstanding physical effort from both and a heartbreaking finish when the Czech simply couldn’t continue. The obvious answer is Rafael Nadal over Daniil Medvedev, but the hipster in me won’t allow me to go for this one. The quality was never really great, but the entertainment value – unbelievable, no? Shingo Kunieda tackling Alfie Hewett in the men’s wheelchair was pretty amazing too, especially that peaking third set from the Japanese legend.

I don’t think there was one that truly disappointed me. Diede de Groot beating Aniek van Koot was lopsided, but still enjoyable as the powerful display by last year’s Golden Slam winner gave me a great insight into her game. Watch wheelchair tennis, folks! It’s really good. Can’t recommend the junior events enough either, a glimpse into the future is always great.